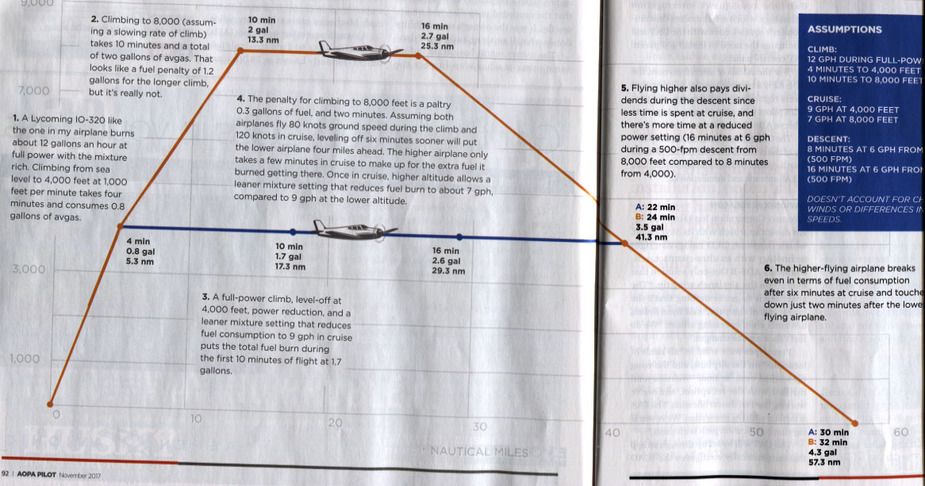

In the Nov 17 US AOPA magazine there is an interesting article on whether it is worth climbing higher. Everybody knows that turboprops and jets have to in order to get any reasonable fuel efficiency but many/most people doubt this for pistons.

It turns out that the penalty for e.g. a 8000ft climb is almost nothing compared to 4000ft.

That’s unless you have a headwind

The small IO-320 is a poor example though, with 12 GPH in climb and 8 GPH in cruise. In an IO-550, it’s 28GPH in (initial) climb and 13 GPH in normal cruise, hence a very different relation between the two. Those 28GPH climbs really hurt in your fuel calculations.

Anyway, cruise altitude is usually dictated by much stronger factors than ultimate fuel efficiency: turbulence, airspace structure (both VFR and IFR), clouds, icing, oxygen.

Generally, on longer flights, I tend to climb a bit higher rather than lower, mostly because of ride quality. It usually pays off to go a bit higher, and enjoy the better ride, even if it burns a tad more fuel or if it makes the flight take a bit longer.

The exception is when sightseeing is a factor, but then, one tends to keep those flights rather short anyway. Generally, it’s early in the morning or late in the evening when one can fly down low and still have a smooth ride. These are the most beautiful flights of all.

This is not a surprise. All one has to do is read the POH and do some work on the performance tables.

In larger airplanes, there is a table referring to the optimum cruise level vs distance. No small airplane manufacturer has bothered with this kind of calcs as far as I know but one can do them.

Most of our non turbocharged airplanes are most efficient at around 8000 ft PA. Therefore, most of the time, a climb to 7-9k ft will pay out pretty fast unless it is really a 20 minutes trip. Also most of our planes will reach these altitudes fairly fast and only loose climb performance over 10k ft.

I am typing on my tablett here sitting on the porch of my vaccation bungalow in Gran Canaria, so I don’t have my tables with me, but from memory I know that the max range and speed sweetspot of my plane lies somewhere at 7500 ft. So my goal is to fly at this altitude whenever I can. In the case that there are unpleasant conditions there, I rather fly higher than lower. The few longer trips I did were flown at 12’000 t0 15’000 ft, but this is going to change now as I have a small child. But up there, it is much quieter and most clouds are below already.

Honestly, I donˆt know where this scare of flying high comes from. It is obvious that flying higher than lower is safer in the context of options you have in terms of engine trouble (oxygen issues aside). But many people are scared of altitudes, I recall a thread where some UK pilots wrote to ask if anyone had ever reached 10’000 ft. Again, I see a problem there in PPL training. Flying high means mixing and a lot of FI’s are scared of that, which imho disqualifies them as instructors for insufficient technical knowledge.

Peter wrote:

In the Nov 17 US AOPA magazine there is an interesting article on whether it is worth climbing higher. Everybody knows that turboprops and jets have to in order to get any reasonable fuel efficiency but many/most people doubt this for pistons.

For aircraft with normally aspirated piston engines the only thing that really matters performance-wise is choosing the level with the most favourable winds.

The reasons pilots fly low, are many fold, but I don’t think fuel really comes into their consideration.

1. Most pilots only fly short flights. Circa a hour is normal in the rental scene. With these, given that 5 mins on both ends is in the circuit, it’s hardly worth the effort to climb higher.

2. Most pilots want to see the place they are flying over, particularly so if doing a short flight. For most, GA is about the sensation or dream of flying rather than actually getting to a destination.

3. Most pilots learn to fly lower in the training environment, and simply never change their habits. In most countries as you go higher you get more controlled airspace. In the UK, it’s hard to go very far at 4000ft without encountering controlled airspace. Instructors teaching dead reckoning don’t want to be in a controlled environment with ATC changing the plan. They want their student to be able to practice following a predetermined heading and altitude and learn to correct the deviations from planned track. They can’t do this if ATC is constantly changing their plan. Also the instructor wants to let the student recognise their own mistakes and correct them. So they don’t want to step in too early and point out the errors. Better to wait for the student to recognise this themselves. This isn’t really possible in controlled airspace or outside controlled airspace when there is controlled airspace in the vicinity. Hence it’s better to stay lower where there is more class G.

4. Many pilots are uncomfortable asking for controlled airspace transits. So they prefer to stay in class G when they don’t need to ask for entry. Staying lower means more class G.

5. For VFR pilots the weather can be a big issue. If you plan a VFR flight at 10,000ft and on the morning of your flight you realise you can’t get above 2500ft, then your plan has to change drastically. All those danger/restricted/prohibited areas, nature reserves, ATZs and CTRs that you were hoping to overfly suddenly come into play and your route needs a lot of review and possibly rearranging. If you plan at 2000ft, this issue never arises.

6. For VFR pilots controlled airspace is a real issue. The higher you go up the more controlled airspace you encounter. There is nothing more annoying than to spend 20 minutes climbing to 10000ft only to have an airspace transit denied, and find that you have to descend (perhaps while orbiting) down to 2000ft to go under it. It only thanks one such refusal on your route to make the climb not worth it.

7. For renters, fuel savings doesn’t really play a part, as they generally rent wet. So in the initial example, they would be paying for 2 extra minutes rental! It’s cost them rather than a saving!

For me, fuel doesn’t really come into it. The two advantages that do it for me are:

1. Stay higher over open water if I’ve time to climb before a water crossing, and

2. I find that airspace transits are often easier to negotiate if you are higher.

Colm

Great post Colm.

Is wet rental common in the USA (the original article context)?

Again this illuminates the US-Europe difference: a US magazine is focused mostly on owners.

Peter wrote:

Is wet rental common in the USA (the original article context)?

Yes, wet rental is common in the US. My US rental experience is very old but I don’t remember any other kind of rental arrangement.

Peter wrote:

Is wet rental common in the USA (the original article context)?

Yes, never came across dry rental in the US.

This, however, is nonsense, at least outside the UK (which must have the craziest airspace structure on the planet):

dublinpilot wrote:

6. For VFR pilots controlled airspace is a real issue. The higher you go up the more controlled airspace you encounter. There is nothing more annoying than to spend 20 minutes climbing to 10000ft only to have an airspace transit denied, and find that you have to descend (perhaps while orbiting) down to 2000ft to go under it. It only thanks one such refusal on your route to make the climb not worth it.

It’s the inverse – the higher you go, the LESS airspace issues you have, as you overfly all the various airport control zones, nature reserves, etc, etc.

Personally I enjoy flying higher more than bimbling about, so usually go to between 8k and 10k where the NA airplanes I fly (C182 and C210) are happiest. Fuel doesn’t come into the equation, as the club airplanes I fly are billed wet.

The interesting thing, and counter-intuitive, is that max range is actually independent of altitude – it’s the same at 1000ft as at 20000ft.

For example the attached is the Foreflight performance profile for a C182 flying Shoreham to Cannes at a high power cruise right now.