Peter wrote:

would suggest a 10% engine failure rate which would rapidly ensure we are all broke, or deadSome concrete examples would be useful info.

I survey well over 100 aircraft a year, with some bein twins, so the number of engines is probably N of 150 a year.

I really don’t have the time to go through all of them for some serious statistics and honestly it does not interest me.

My remark was simply pointing out that JUST BECAUSE an engine is over 50% of the manufactuere’s suggested TBO does NOT mean it’s “likely” to fail. Fuurther , the “1 in 10” W A G was pertaining only to engines over 50% TBO and it’s very likely more on the order of 1 in 100 , but once again, just a WAG since I really don’t have any interest in crunching the stats.

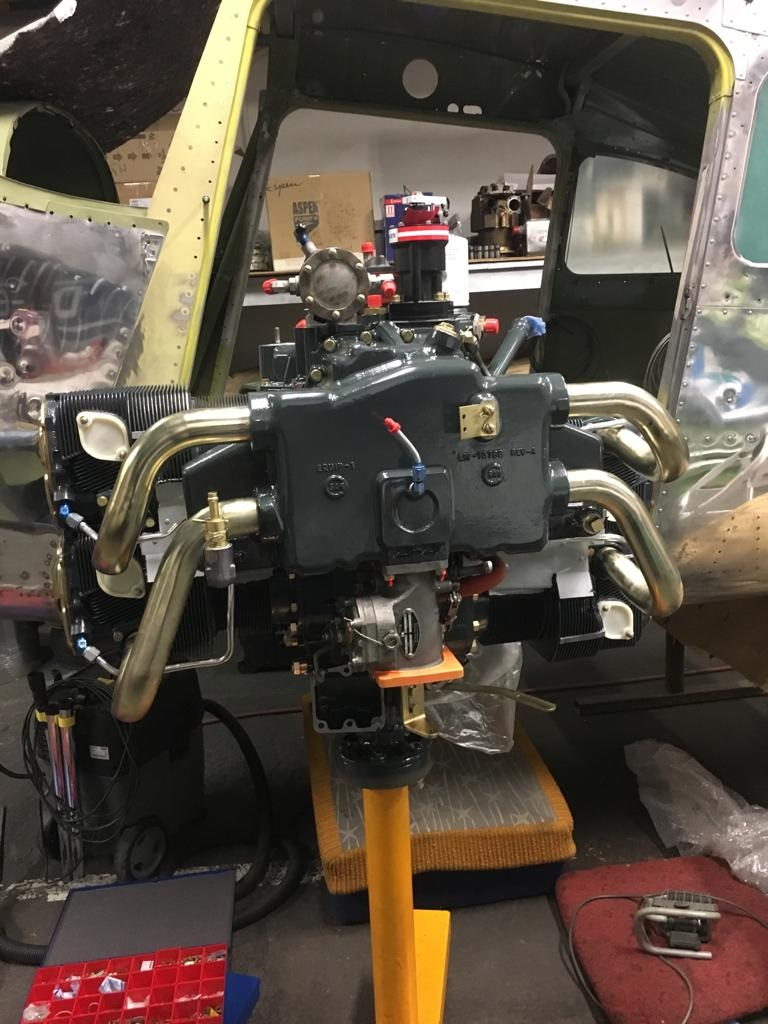

And finally the money shot

Very impressive photos and thank you for posting them

Glad you will be getting back in the air after all that!

Which engine shop did the work?

Jiri Fliger in the Czech republic – Quality work – slow but very high quality, I will pick the plane up in the next week or so – looking forward to flying again.

aidanf123 wrote:

but if I was to buy a plane in the future I would discount the value of the engine down to zero at mid time and even faster if the usage was low.

Could you elaborate/specify this more please?

Let’s say an engine has done 150 hours in the last 4 years… = engine value ‘0’ = deduct cost of remanufactured engine from asking price?

Just to be clear, on what basis was this engine deemed to be unairworthy?

If it was still producing full power, decent compression, reasonable oil pressure and consumption, exhaust valves not overheating, less than 1/4 teaspoon of metal in the filter, oil analisis steady, I’m not sure that I would tear it down just because it was partly worn.

All the valve guides were out of tolerance, when we removed the cylinders the cam was damaged with some minor corrosion and 2 of the lifters were starting to spall.

The compressions were good, oil pressure etc, if it had not been for the valve guides and the subsequent sticky valves it might have run for another couple of hundred hours, but for my peace of mind I am happy we went with the full teardown and repair.

I have a motor and accessories now which is prety much good as new, that makes flying a great deal more pleasurable.

WIth respect to the previous question, if an engine has done 150 hours in the last 4 years I would say the usage is low and the engine would be suspect, and it depends on the pattern of usage – running up 40 hours of usage over the summer months then leaving it idle for 6-8 months is obviously different than taking it up for a run once a week over the entire year.

Getting an engine to TBO is all about regular usage and engine operating temperature and it is all about illiminating the two biggest engine killers corrosion and lack of lubrication.

The UK’s biggest Lycoming fleet has almost all its engines make TBO simply because of high annual usage and getting the engine up to a good working temperature and because of the high usage the oil gets changed very regularly. As you might guess camshaft failure is practicly unknown to them. Some of this credit must go to the overhaul agency they use who are producing a high quality product.

Back in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s when CSE at Oxford rand a training school they had an approved maintenance program for their Lycoming engines that ran the bottom end to 4000 hours with the cylinders changed at 1000 hours and all this on straight oil ! once again this was a high usage operation that got its engines up to temperature and kept them there for a considerable time with the oil being changed regularly.

It follows that the best way to destroy an engine is to run short trips that don’t get the engine hot, leave the oil in the engine for months on end and don’t run the engine for weeks. The combination of moisture held within the oil and the lubricant slowly dropping from the camshaft are the killers as corrosion forms on the dry camshaft and when the engine does get started it runs dry untill the oil pressure builds sufficiently to get oil to the cams.

So the question is how to mitigate the problems of low usage ? First I would make sure the aircraft always gets enough flying to get the oil temperature to 180F for the best part of an hour. Second use a quality oil with a corrosion inhibiter. Third, change the oil at three months intervals. Forth , when you change the oil if you can’t fly remove the spark plugs and spin the engine on the starter until you make good oil pressure.

I’m not sure about using cam guard but I can’t see it doing any harm .

Most of this won’t be new to many of you but it’s worth saying for those new to aircraft ownership, I guess the bottom line is that an aircraft engine can cost you as much sitting around doing nothing as it can being flown.

Peter wrote:

Yes exactly, and the “suspected corrosion” cam+follower disintegrations are really rare on engines which have a proven regular flying record. In fact I have never heard of one.

I’m sure I’ve mentioned here the C172 that I learned to fly in – it was in out flying club in Houston and flew 1000 hours a year. I had to switch planes during my initial training due to the engine needing an overhaul at around 1200 hours due to camshaft spalling. However, that was a bit of a special case because it was the O-320-H2AD (where AD seems to mean ‘airworthiness directive’) which has a higher incidence of this kind of thing happening (which is too bad, because otherwise it’s a good engine and has a lower fuel burn than earlier O-320 engines).