Archie wrote:

I assume by “glide back” you don’t actually mean a turn back, but a glide to land straight ahead. I think it is foolish to assume you can do this safely without injury as I pointed out earlier. There may be forest, ditches, rocks, houses, cars, water, fences in the way.

Yes, glide back to earth, not the departing runway – we land straight ahead following EFATO. This should be a safe and injury free event, unless you hit something, which is not an aircraft performance issue, but rather bad planning (takeoff path) or bad luck (the hard thing was there, and nothing you could do about it). However, a properly conducted takeoff should always have a safe power off, land straight ahead option (assuming suitable area to land in). Other than a possible brief period before the obstacle is cleared, an engine failure during a normal takeoff should leave the aircraft retaining enough energy, and controllable to return safely to earth.

I get your concerns and I think they are valid. However I also think that your concerns “concern” pilots that do not fly the plane in accordance with the POH/AFM/normal envelope and don’t have the proper response to an engine failure.

Pilot_DAR wrote:

Those showoff pilots who climb away after takeoff, hanging on the prop with no obstacle, are failing this miserably.

Pilot_DAR wrote:

A short field performance chart is going the show the distance required to clear the 50 foot obstacle, and when over the obstacle, you will have the speed to land back safely. You can clear the obstacle in a shorter distance, but a safe glide back will not be possible. For that reason, the manufacturer will not provide that data, even though the plane could be capable.

Rwy20 wrote:

No, he is not. Pilot_DAR talks about a trajectory on takeoff which would allow you to keep flying if the engine stops, as opposed to plummeting to the ground.

Archie wrote:

You simply cannot assume that you can get to 50 ft then abort the take-off and land back without having a serious mishap. TODR is the take-off distance required to a screen height of 50 ft.

Slight misunderstanding perhaps. If you are performing a short field takeoff, and you have an engine failure over the obstacle (50 feet), a safe land back should be possible if: You achieved a speed adequate to enter and maintain a glide, and there is a suitable landing area ahead. This has happened to me, as an engine failure after takeoff, and I landed with no damage ahead in the next field, just after the engine quit over the obstacle trees. The key is maintaining a suitable speed.

A short field performance chart is going the show the distance required to clear the 50 foot obstacle, and when over the obstacle, you will have the speed to land back safely. You can clear the obstacle in a shorter distance, but a safe glide back will not be possible. For that reason, the manufacturer will not provide that data, even though the plane could be capable.

Rwy20 has presented (thanks very much) a gold mine of understanding as to this situation with the referenced article. If you are going to leave ground effect in a minimum performance situation (like a short field obstacle clearance) you really should understand this. I have done the testing. It was the most un nerving flight testing I have ever flown. I really did fear I would crunch a Caravan (the one pictured earlier). The increase in drag was so much that the plane could no longer achieve the minimum required rate of climb for approval when flown at the POH "after takeoff speed. To achieve approval, my only choice was to after takeoff climb at a slower speed (80 KIAS, rather than 87 POH value). It worked, the required climb rate could just be achieved, but now I was required to demonstrate an engine failure land back. I could not do that – I would have bent landing gear in the hard hit. Approval was conditionally issued with this shortcoming considered. I learned a few important lessons vividly!

For those wishing to further their understanding of the article Rwy20 has kindly posted, do some reading on “height velocity curve” or “dead man’s curve” for helicopters, and understand the concept. It’s about the same for fixed wing aircraft, with the variation that a helicopter can store energy as rotor RPM (up to 110% of normal RPM, build up during the descent) and airspeed. An airplane can only store this energy as speed. This stored energy will be required to arrest the inevitable rate of descent during the power off arrival.

This is an important, yet poorly understood topic within the powered flight community. It is because of this poor understanding that all forced landing training I do while training others will conclude in a touchdown, particularly for water landings. It’s fine to practice gliding down to 100 feet, then powering away over surprised sheep, but that left the lesson very incomplete. That’s a whole other topic worthy of it’s own valuable discussion, and thread drift tot he original topic here. But it all goes to planning your departure to be most safe – clear the obstacle if there is one, clear it with a reserve of safety if you can. If you must clear the obstacle at the cost of the understanding you cannot maintain a safe glide back speed, understand that, and minimize your time in the risk zone. Those showoff pilots who climb away after takeoff, hanging on the prop with no obstacle, are failing this miserably.

Archie wrote:

Hang on, we have a serious misunderstanding here. You simply cannot assume that you can get to 50 ft then abort the take-off and land back without having a serious mishap. TODR is the take-off distance required to a screen height of 50 ft.

What you are talking about is the total sum of distance = TODR + LDR, which is the take-off distance required to 50 ft, followed by a landing again from that 50 ft.

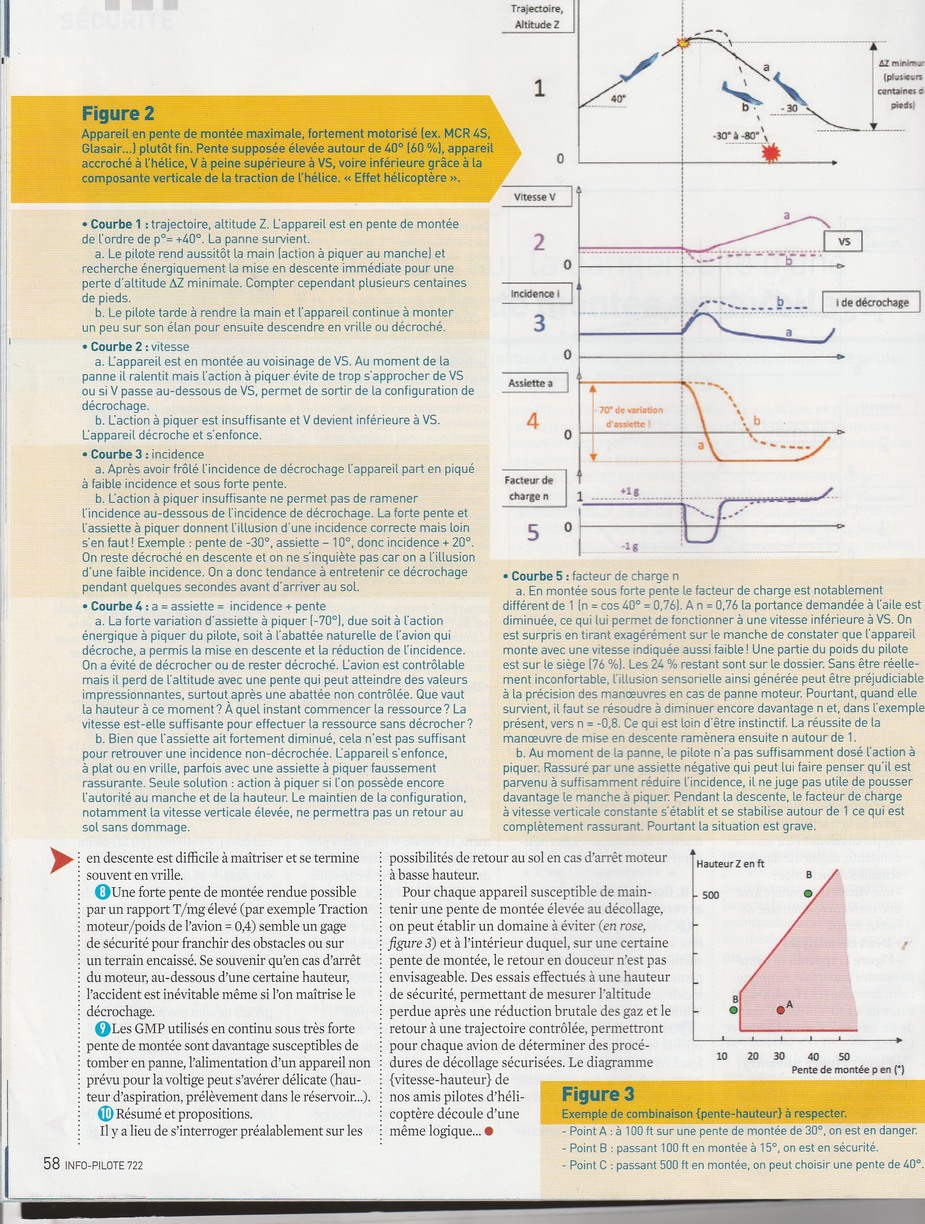

No, he is not. Pilot_DAR talks about a trajectory on takeoff which would allow you to keep flying if the engine stops, as opposed to plummeting to the ground. There was a good article in the May 2016 issue of “Info Pilote” explaining this; unfortunately in French. But if you look at diagrams 2 and 3, you should be able to understand the concept even without reading the text (“facteur de charge” means “load factor”). This is especially pronounced on planes with good motorization and highly charged wings.

In diagram 3 you can see that with more altitude, you can use a steeper climb. But hanging behind the prop (in “helicopter effect”) low to the ground is a recipe for disaster, no matter how much runway you still have in front of you, because you won’t get the nose down before stalling and spinning in.

Pilot_DAR wrote:

It is a certification requirement that an aircraft be able to be safely landed back after a departure engine failure at 50 feet – as long as the pilot achieves the speed needed to accomplish this. Upon reaching, and maintaining that speed, the aircraft can be landed back without damage (surface notwithstanding). Failure to achieve that safe speed is a recipe for a crash if it quits.

Hang on, we have a serious misunderstanding here. You simply cannot assume that you can get to 50 ft then abort the take-off and land back without having a serious mishap. TODR is the take-off distance required to a screen height of 50 ft.

What you are talking about is the total sum of distance = TODR + LDR, which is the take-off distance required to 50 ft, followed by a landing again from that 50 ft. And using that as your personal margin. All I can say it that you are applying a margin that is way outside of POH/AFM specifications. Which is not necessarily a bad thing.  However you don’t need to fly like a test pilot to achieve the TODR figures in the POH/AFM. Just being an average pilot will make these work.

However you don’t need to fly like a test pilot to achieve the TODR figures in the POH/AFM. Just being an average pilot will make these work.

Unless you are talking about some unusual certification process that I have never heard of…?

Jacko wrote:

I’m happy with my definition of “short” and “soft” fields, especially for places where no other aircraft has ever landed, but does anyone feel inclined to offer a better one for established or partially improved landing strips?

But let me ask direct questions as that might clarify a few things as I still don’t get your decisionmaking.

When you say: “a short field is one where the departure cannot be aborted without injury as soon as the pilot determines that obstacle clearance is not assured”

- How do you determine that obstacle clearance is assured?

- When do you determine that obstacle clearance is assured?

(I exclude an off-airport landing as it has a high chance of injury). ……

- at every take-off there is a point where you cannot abort anymore without injuryQuote

I don’t see the link to injury. It happens on improved runways too. I have thousands of unprepared runway takeoffs, and thousands more off the water, including a few real engine failures, and many simulated ones, and never an injury nor damage. I regularly witness alarming displays of poorly thought out airmanship with pilots feigning “STOL” takeoffs with needless steep climbs after leaving the ground, which are much more likely to result in an injurious crash in the case of an engine failure. This is because pilots are allowing the aircraft to climb away at an airspeed too slow to enter a glide from which a successful flare could be made in time. And all this within the confines of perfectly suitable runways.

It is a certification requirement that an aircraft be able to be safely landed back after a departure engine failure at 50 feet – as long as the pilot achieves the speed needed to accomplish this. Upon reaching, and maintaining that speed, the aircraft can be landed back without damage (surface notwithstanding). Failure to achieve that safe speed is a recipe for a crash if it quits.

When I think back, I would estimate that 999 out of 1000 takeoffs I do would employ a soft field technique, to one employing short field. It is rare that I depart from a runway so short for the aircraft that I worry about having space to clear the obstacle. But, every now and then I’m cautious in this respect. In all other cases, my technique will be soft field, simply to save wear and tear on the landing gear. In a few of those cases, I will use a soft field technique because the runway actually is soft.

I’ve never heard of a requirement to remain within gliding distance of an airfield, but if it’s a rule somewhere, okay – it certainly is not in Canada!

Archie wrote,

I exclude an off-airport landing as it has a high chance of injury

Is this something the Dutch authorities tell GA pilots just to frighten them?

Anyway, from a US or UK perspective, it’s just scaremongering. Searching the NTSB accident database for off-airport GA landings (of which there must be tens of thousands without incident every year) we see very few accidents and even fewer injuries.

I’m happy with my definition of “short” and “soft” fields, especially for places where no other aircraft has ever landed, but does anyone feel inclined to offer a better one for established or partially improved landing strips?

what_next wrote:

If that would be true, no commercial operation would ever get approved.

Obviously it is true. Unless you remain within glide distance of an airfield at all times… (or in a twin). Commercial ops get approved no worries.

Pilot_DAR wrote:

In most cases with proper runway availability, the take off can be abandoned airborne, and a safe return made. I’ve done it many times (a couple ’cause I had to, and many during testing). It is a certification requirement. However, it does require space.

No, same as above. Unless you remain within glide distance of the runway at all times… (I exclude an off-airport landing as it has a high chance of injury). Not sure how certification requirement comes into play?

But perhaps Jacko needs to explain a bit more.

Jacko wrote:

a short field is one where the departure cannot be aborted without injury as soon as the pilot determines that obstacle clearance is not assured

Pilot_DAR wrote:

The “ground” run portion of the takeoff distance is the easy part.

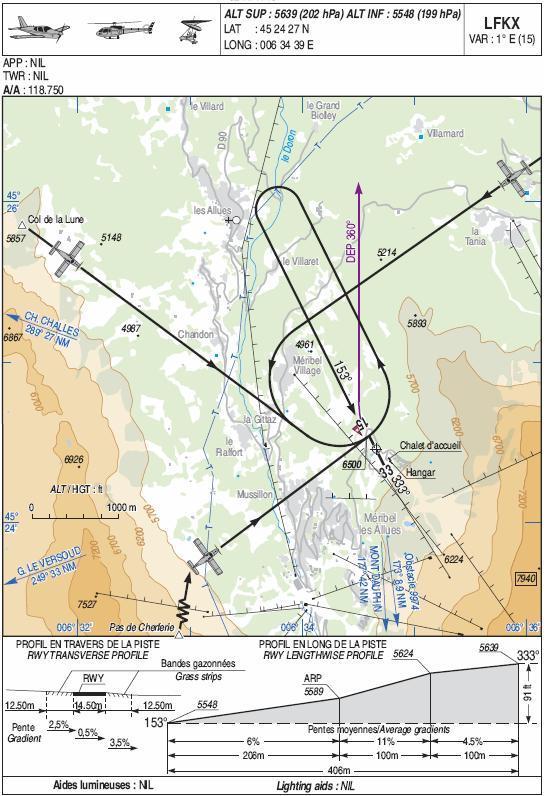

It’s fair to say that none of these is “short” in absolute terms, but I don’t think it is all that easy to use typical POH figures to calculate the ground run at this airport:

or here (270 m @ 10% slope, 5,600 ft AMSL):

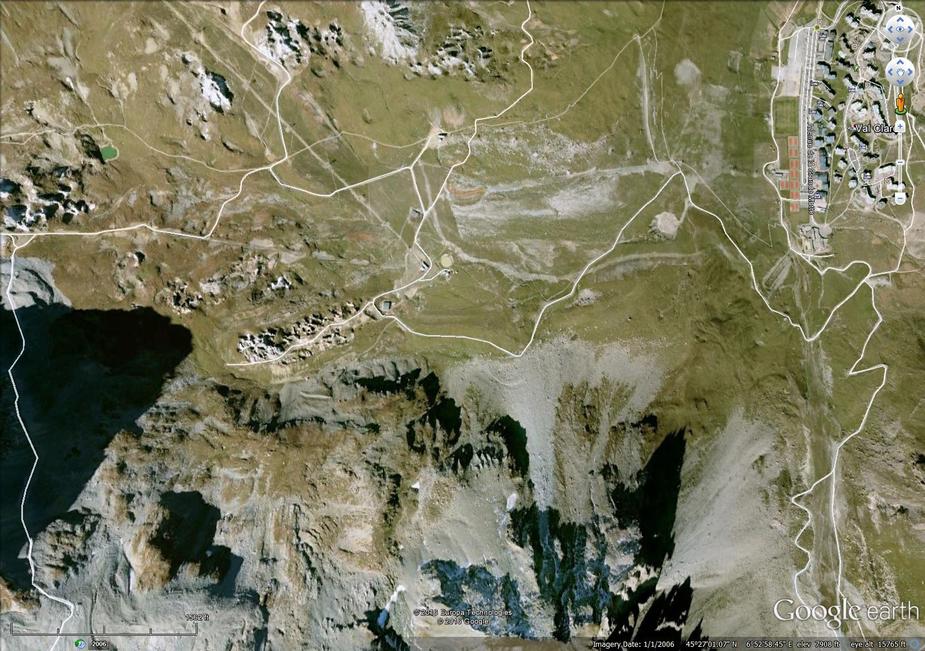

or here (370 m @ 14% slope, 8,000 ft AMSL):

RobertL18C wrote:

Would the rule of thumb that you abort take off if you haven’t reached 75% of your lift off speed at the half way point, work for soft runways?

I think that’s a pretty sound rule of thumb, as long as there is not too much downslope to stop and as long as the runway isn’t particularly soft.

I really don’t trust very soft ground. Even with 31" tyres, once a wheel sinks to the rim, you’re in the civil engineering business. On beaches, intertidal sand can be prone to liquefaction. It’s usually OK as while trundling along in a straight-ish line, but swing the tail around too sharply and the inside wheel suddenly makes its own swamp…

DavidC (of this parish) posted a nice little video showing a soft field takeoff (second half of the video). With commentary from Jim Thorpe.