I have the impression that most planes can be loaded outside the envelope before reaching max gross.

The question is how bizarre a situation is required to do it.

Mostly not bizarre at all!

The TB20 is unusual. You would need a 40kg (UK size 6!) pilot, rhs empty, 2x 125kg men in the back, 65kg in the boot. Latter two are structural limits per POH. IOW impossible in reality. The IR examiner I had for the IRT didn’t believe me initially but checked it himself and agreed.

I once had an experience loading a case of wine in the baggage compartment of a C172. You will know that the trunk (or boot for the English readers) is separated in two parts, one smaller wedge at the rear end and the big compartment in the front. Since the wine case fit nicely in the small wedge part, I thought it would be a great idea to put it there – so it would be secure against turbulence and in order to gain 1-2 kts of “free” speed. Two people in the front and no-one in the back seats.

On lift-off I learnt very quickly that the neutral trim position doesn’t suffice in this kind of loading. Luckily I was quick enough to push the yoke forward and trim downwards. I think it wasn’t worth the risk for 1-2 kts.  Even though on paper, this was within the W&B, I am not sure if it was really.

Even though on paper, this was within the W&B, I am not sure if it was really.

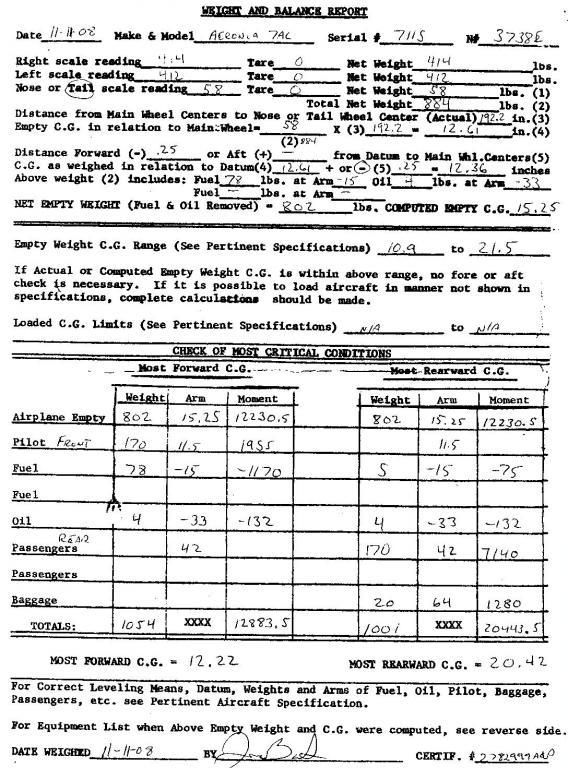

My experience has been that the most screwed up things in aviation are aircraft W&B documents (which usually follows a screwed up weighing). The result can be that no matter how diligent the pilot, mis loading can occur. This is one reason that is is very good to “know” the plane you’re flying. If you have doubt about how compliant is the W&B, either approach your loading with extreme caution, or don’t fly it until you are sure that the stated empty weight and C of G are accurate.

One of my scary moments was test flying a modified C 185. It had been purposefully loaded to the aft C of G limit by a very competent organization. I flew the required spin tests, and spin recovery was very difficult – certainly not compliant. I took it back and told them something was not right. It turned out that they’d made an error, and the load I was carrying was 4 inches aft of the aft C of G limit. We reloaded, and it spun fine.

Flying behind that aft limit is not immediately dangerous, but it will severely reduce spin recovery ability, and otherwise make for sloppy handling. This is why some pilots get away with it for a while, though mis loaded, they purposefully, or accidentally avoided the conditions of flight which were immediately dangerous. Indeed, if you are going for long range, load the plane right to the aft limit (and to remain within throughout the flight) – it’ll go a little faster.

Pilot_DAR wrote:

My experience has been that the most screwed up things in aviation are aircraft W&B documents

That sure is the truth. I need to do new W&B on both my planes because I’ve looked through all the previous calcs, done under previous owners, and I know they’re flawed to some degree. Nobody wants to weigh the plane some approximations and errors build and build.

The calculated CG on my newer plane is right on the aft limit, but there is margin in the loaded CG because I rarely carry heavy bags. A friend has some nice new scales and its on my list for March. He gets asked by many to use the scales, and has an odd policy: he’ll lend them to friends only for nothing, but won’t rent them for money to anybody. That way they don’t get broken which is his major interest.

I think I might have mentioned that I used to do load control for airliners for a living, including some years as an instructor.

I always felt that WnB for small airplanes at the time (still calculating weight x moment and adding up and dividing) was unnecessarily complex for every day use and also the forms used did not tell the user much about it, for most people the CG calc was an abstract figure which had to, when correctly plotted, fit into an envelope.

For the airliners, we had pretty simple balance sheets which could be filled in without ever taking a pocket calculator out of your pocket.

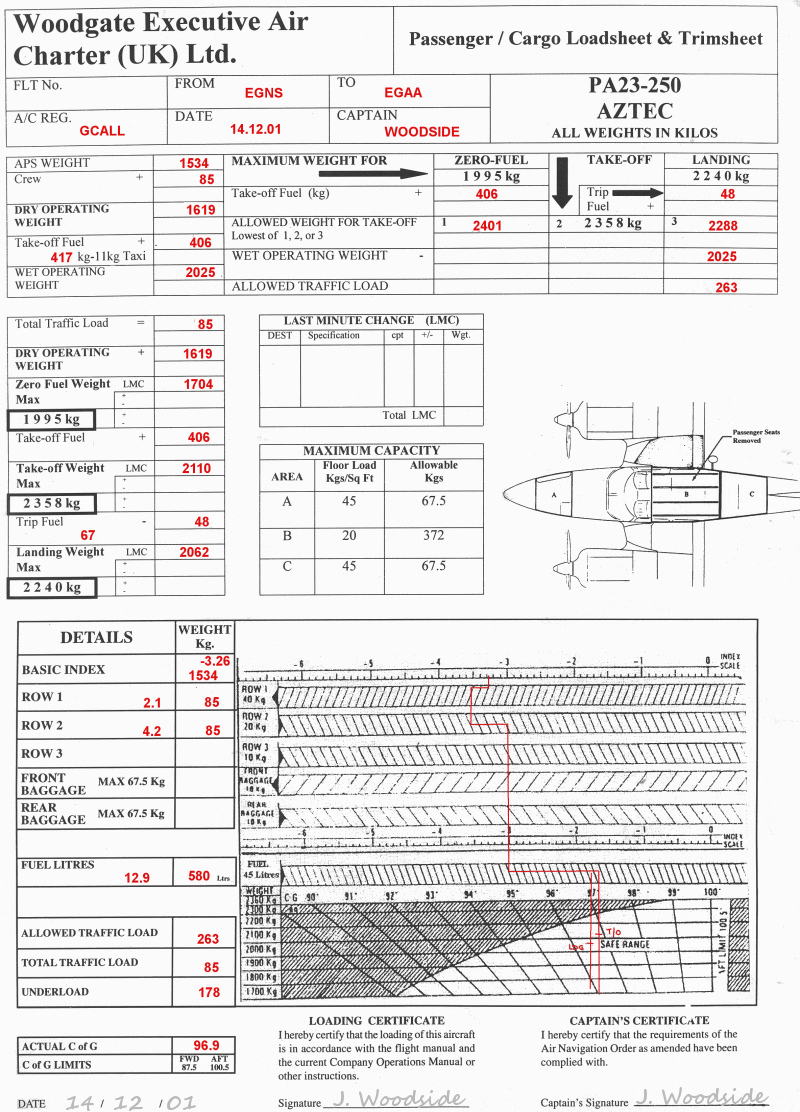

A quick search on the net returned this example of a lovely manual weight and balance sheet for a Piper Aztec.

here is another one for an Airbus 330.

Now, doing one of these never took me more than a few minutes starting when I got the closeout figures to delivery.

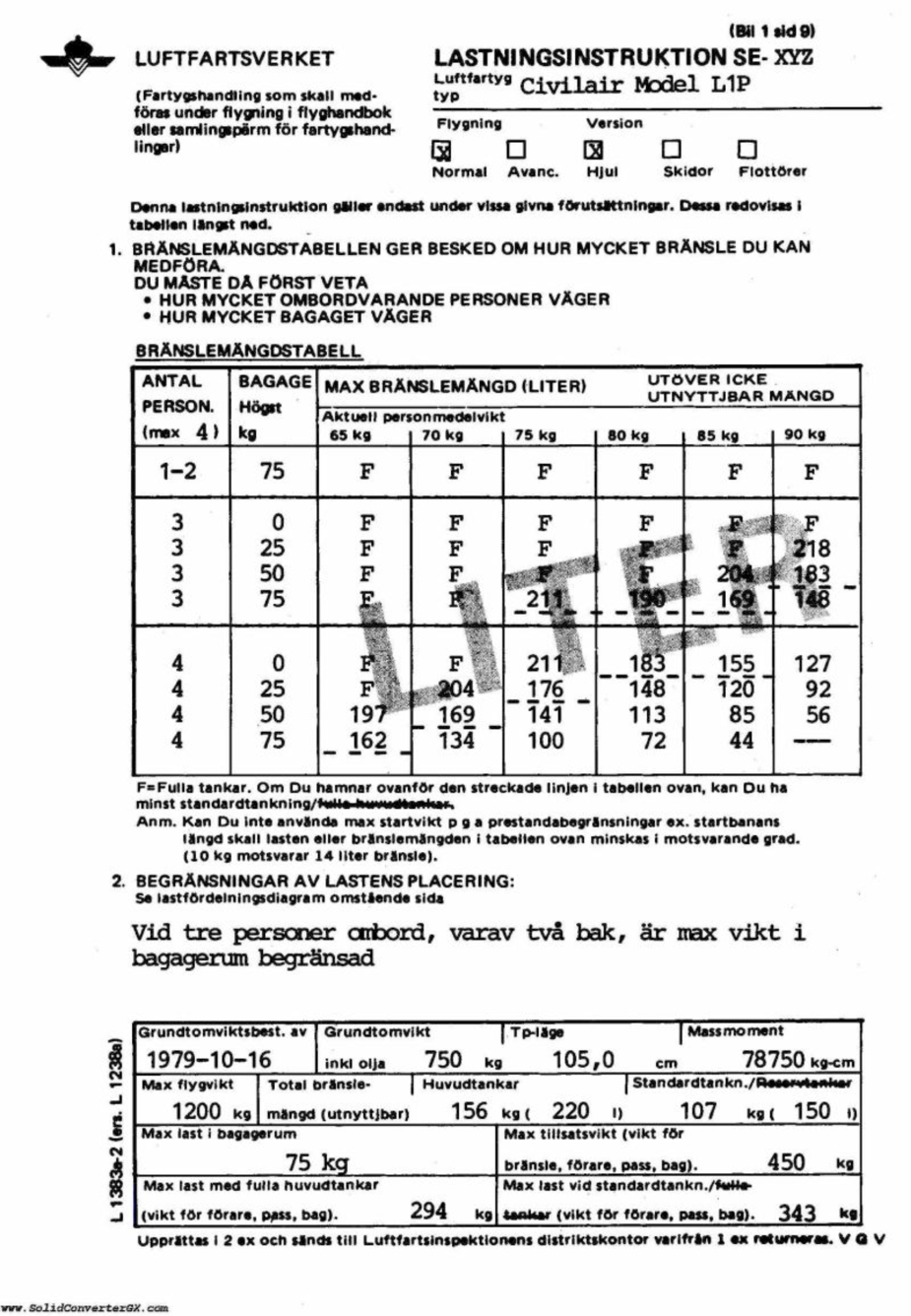

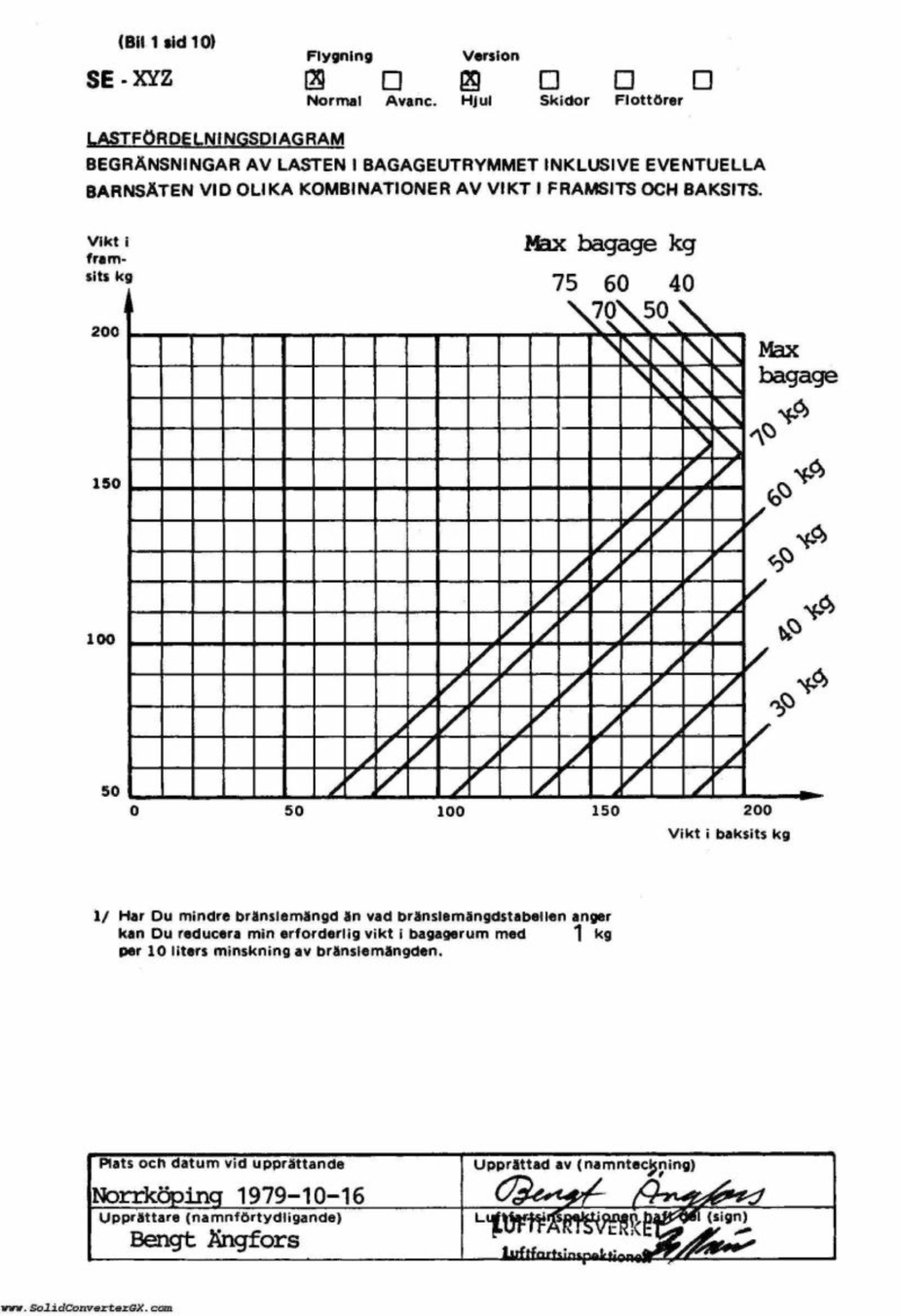

This here however…..

which is a typical example for what even today a lot of students have to work with…. and then transfer the figures onto a graph. All that while the pax are waiting for you to stop fiddling and getting on with flying. Do we really wonder why nobody does this when it is actually needed, namely when all pax and cargo is on board, ready to go?

I think these old and unnecessarily complex forms are the reason that even today people are lazy to do a proper WnB. It is still taught like that and even has to be, but even before computers came along, it would have been much better to create sheets like the Aztec one above for all small planes. They are much easier to use than the multiplication and division thing which WILL cause mistakes.

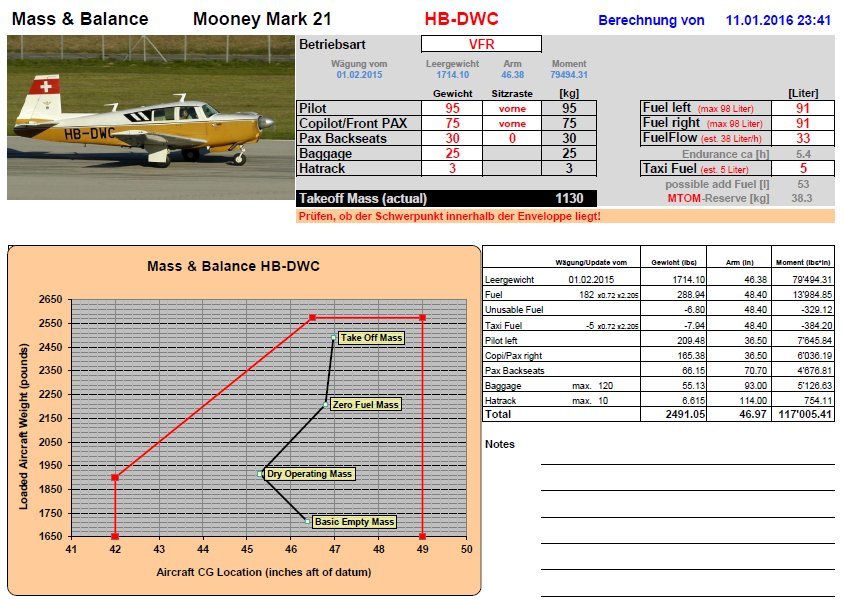

Of course, today we have a much easier world, where we can do this stuff on our PDA’s, smartphones or laptop. My pilots use an Excel sheet which is filled in in 2 minutes flat including starting it up. There is no calculating: Fuel is in Liters, weights in KG. It works on my PC, on my smartphone and tablet. This most recent form even has the original moment/arm calculation on it. All that can be modified are the red figures on top. (Work in progress done by the head FI of our pilot team)

And of course, most people today can do WnB with apps on their smartphone. Or the one in the EuroGa Autorouter. Or …. or …. or… the options are limitless today. Nobody has to work with crappy handsheets anymore.

So is there really an excuse today not to do it? I don’t think there is. It is easy to do, quick to do and can be verified even while your passengers still try to figure out how to close their seatbelts.

When instructing, i had an even simpler little table for every aircraft in the school.it had 4 or 5 values for the four-seater:

– max single passenger weight (in front seat), full tanks (limited by front C of G or MTOW, whichever hapens first)

– max total passenger weight, full tanks (limited by MTOW before even going near C of G limits)

– max single passenger weight (in front row) fuelled to tabs (again limited by front C of G or MTOW)

– max total passenger weight, fuelled to tabs (limited by MTOW)

– max rear-seat weight with front passenger seat unoccupied (limited by rear C of G)

Of course this assumes no luggage, as is the case in training.

So by adding up the passengers’ weight an comparing it against one or two numbers, I could qickly decide if the flight could be conducted within limits. These were PA28, and the differences between individual aircraft were remarkable – all but one were impossible to get out of rear C of G before hitting MTOW, one was limited to 58kg for the student before being outside the front C of G limit, while another one could almost take the entire payload in the front row…

I had a situation once while flight testing a Citabria on floats, where it was required to flight test at gross weight and the aft C of G. The purpose of the flight test was for a gross weight increase approval. While flying solo in the front, it was not possible to put enough weight in the baggage compartment to correctly ballast the plane. If I carried a back seat passenger, I got to gross weight, but not yet to the rear limit. The weight required in baggage compartment would well exceed the limits of that compartment (floor loading being one.) My solution was to determine the station location of the most aft float compartments, and pour in the required amount of water. That’ combined with just the right amount of ballast in the baggage compartment, put me in the correct configuration. I sure got some funny stares pouring water into the floats before my flight!

Another of my projects was the testing and approval of a changed engine mount for the deHavilland Beaver. That new mount moved the engine 9 3/4" further forward, simply to use it as ballast to assure that the normal loading as a floatplane would not put the aircraft behind limits. In addition to the great benefits for the W&B, the longer mount made maintenance on the back of the engine very much more easy! It was a hit, and many STC kits were sold.

http://www.sealandaviation.com/extended-engine-mounts.php

Sadly the very wise Mr. Holmes of the Beaver fame, with whom I had done this approval work, was killed flying an experimental aircraft, with W&B and handling “issues”, which only came to light following his mysterious crash.

While flight testing a Bell 206 helicopter for an aft camera installation, the company pilot and I up front were not enough (maybe I need to eat more pies!). We added the maximum 30 pounds of lead permitted in the nose battery compartment, and thereafter 70 pounds of steel bar tied down to the floor under our heels. The flight testing went fine, but obviously the installation was not approvable with ballast on the cockpit floor (and those battery compartment lead weights are surprisingly rare!). My client came up with an STC’d ballast arm while projected forward from the opposite skid tube, but when I flew, I found an unacceptable harmonic vibration. Ultimately, a whole new external ballast are was devised, and that was what was ultimately STC’d as a requirement to carry the camera. (The same camera was already approved on the Bell 206L, whose longer fuselage just made it without requiring ballast.)

Mooney_Driver wrote:

I always felt that WnB for small airplanes at the time (still calculating weight x moment and adding up and dividing) was unnecessarily complex for every day use and also the forms used did not tell the user much about it, for most people the CG calc was an abstract figure which had to, when correctly plotted, fit into an envelope.