We all know the mantra of allowing the engine to warm up. Peter has raised it in another thread about camshafts.

But there seems to be an amazing difference between people’s practices.

I was thought to warm the engine at 800rpm. But the POH says to use 1500rpm.

Some people seem happy to go once the temperature is off the stops, others want it in the green arc (if there is a green arc). Some POH’s make a definative statement on this and some don’t.

I’m curious about what the theory is behind this. Most talk about letting the oil get warm and spread through the engine.

But am I not correct in thinking that after a few revolutions (first 2-3 seconds of running) that the oil should be folowing through all of the engine and it doesn’t take a few minutes for it to get all through it?

Am I correct in thinking that often these oils get thicker as they warm up (to help with the lubrication) so they still work fine when cold? (Like car oil). So temperature of the oil itself isn’t so important?

Would I be correct in thinking that this is more about expansion of metal in the engine as it heats, and the the proceedure is to allow it to expand at a relatively even pace, and not having some parts expand faster than other bits?

Just curious as to why we do this.

Am I correct in thinking that often these oils get thicker as they warm up (to help with the lubrication) so they still work fine when cold? (Like car oil). So temperature of the oil itself isn’t so important?

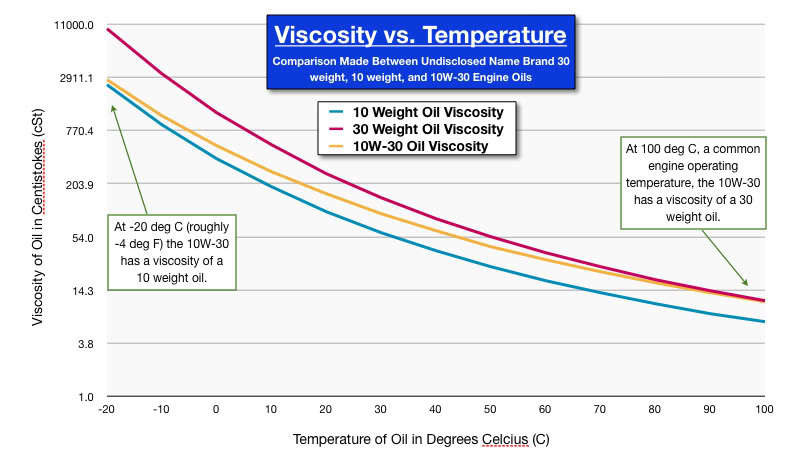

No oil, whether aviation or automotive, gets thicker with temperature. All oils become less viscous when heated, but multigrade ones do it to a lesser degree than straight grades:

If the oil is too viscous, it coats the lubricated surfaces well but doesn’t do much in the way of reducing friction (and wear) because the internal friction in the liquid phase is too high. Conversely, the oil that’s not viscous enough has a low internal friction, but the layer of oil staying on the surface is too thin to mechanically decouple the friction surfaces. Optimal viscosity corresponds to the least friction between the lubricated parts and depends on the design of the mechanism – thus, for example, radial engines require thicker oil than opposed ones.

I have read that differential expansion is important, and could lead to a seizure if a cold engine went immediately to full power. It would perhaps be more important to thoroughly warm a newish engine. I taxi some distance, and usually have to hold. With an engine beyond 1/2 life, I accept the needle starting to move. (Cont. O 200 and multi grade.)

I am not an engine expert but there are a number of resons to run the engine until it is warm:

- Cold oil is very thick and many parts of our engine are lubrictaed with sling oil only. So even if you have oil pressure that does not mean all parts get oil.

- Fuel might condensate on cold parts of the engine altering the mixture and the cumbustion so the engine will not deliver full power.

- The engine parts are calculated to match when they are all at temperature. During warm up there might be more friction which is made worse when running at full power.

- Finally take off is a very critical phase and unfortunately many engine problems just happen there. In general engine problems will often surface when some condition changes. So I think it is a good idea to take off with an engine that is running in a somewhat stable state at constant temperature etc. than an engine which is just heating up.

So if you can try to avoid rolling take offs. Better stand on the brakes run the engine at full power for a moment, make sure that all is fine then release brakes. If the engine is running in a constant condition for a moment chances are much higher it will continue to do so. Half way down the runway at speed is a bad time to realize the engine is somehow not producing full power…

So if you can try to avoid rolling take offs. Better stand on the brakes run the engine at full power for a moment, make sure that all is fine then release brakes. If the engine is running in a constant condition for a moment chances are much higher it will continue to do so. Half way down the runway at speed is a bad time to realize the engine is somehow not producing full power…Quote

My opinion differs on this. It’s true that you would rather avoid getting airborne with an unhappy engine, but for those few types which can get airborne at partial power easily, they usually use so little runway that you’d have lots left ahead if you wanted to land back. Otherwise, you’ve got the power at maximum still short of your abort point.

In respect of warming up, Lycoming says “…. Avoid prolonged idling and do not exceed 2200RPM on the ground. …. Engine is warm enough for takeoff when the throttle can be opened without the engine faltering.”

So no to the full power on the brakes for Lycomings.

I plug my engines in to warm them up, when the air is cool. Easy starts and oil pressure right away. This corresponds to Lycomings instruction to preheat in extreme cold weather.

What about the engine coolant temperature?

I always wait for all engine gauges to be in green, and the engine coolant temp takes longest to move to green.

One could argue that the colder the coolant fluid is, the more heat it can transfer, so there is no need to wait for the coolant fluid to get warm if the engine and oil temp are in the green??

This is on a Centurion 2.0s engine btw…

It’s full IMC-Stephen King weather beyond the door of the hangar, so it’s altogether nicer to sit in the warm and indulge a mild John Deakin addiction

I note his strong feelings about engine startups and high rpm…

On starting, please don’t let that engine roar into life, and go straight to some high RPM. This may be the single most damaging thing you can do to an engine, not to mention whatever is behind you. Most of the oil will have oozed out from in between the surfaces inside the engine, and metal-to-metal contact is always bad. Many experts feel that virtually all the wear in an engine comes from starting, and I certainly agree it’s likely. One trick I use is to shut down at about 800 to 1,000 RPM, then never change the throttle setting until the next start. The cold engine should start gently and then come up to that same RPM slowly. As the oil pressure builds and starts lubricating the bearing surfaces, and the pistons and cylinders come up to operating temperature the RPM will build up to that same RPM range. That’s plenty of RPM for the crankshaft to splash enough oil on all the moving parts inside the engine case.

The full article is here Startups and Runups

Without having read the full article, this

shut down at about 800 to 1,000 RPM, then never change the throttle setting until the next start.

depends on the type of engine. On my Rotax 912, cold starting is with throttle fully closed, choke wide open.

And back to the opening subject: on said Rotax 912 there is no discussion, all documents agree that oil temp must be at least 50 degrees C before taking off.

Before starting, I always rotate the prop a few turns by hand, to pump a bit of oil around.

I was taught to warm the engine at 800rpm. But the POH says to use 1500rpm.

That must again depend on engine type. I think the pain point is to not have it run too slow, that would make the running rough (which is especially bad with limited lubrication) and also produce little heat. My run-ups begin at 2500-3000 rpm, slowing down to 1800-2000 as engine warms up. Mind you this is a geared engine with max rpm=5800.

I think the above is all correct to varying degrees

I think Deakin has it right. The splash lube system on the Lyco camshaft needs a gentle startup, though obviously less so if you fly regularly and use Camguard which makes the stuff stick a bit more.

Another thing is that you need to give both halves of the fuel system (drawing fuel from both wing tanks) a proper test, before getting airborne.

So even if you could get airborne 30 secs after starting the engine, it would be a really stupid thing to do because most planes will do that with the fuel selector in the OFF position

Another factor is that most alternator setups will not charge the battery at 1000rpm, hence you get the 1200rpm recommendation (TB20, etc). My alternator starts to charge at 1100rpm. But there is a tradeoff to be made because the plane will taxi a bit too fast on flat tarmac at 1200rpm, especially with a tailwind…

I have read

Engine is warm enough for takeoff when the throttle can be opened without the engine faltering.”

in the past but cannot believe it was written by an engineer (at Lyco) because why would the engine falter, other than the internal grinding together so hard that the power produced by combustion cannot overcome their friction? It makes me cringe to think what is happening in there

Quote Before starting, I always rotate the prop a few turns by hand, to pump a bit of oil around.

What’s the difference between this and the first turn of the starting motor doing the same thing?