I know nothing about aerial archaeology (wikipedia), other than seeing a few hut circles flying over Dartmoor. Many years ago a famous archaeologist was being flown over the local area in a C182 on a particularly dry summer, and the club got a few complaining phonecalls (“but it’s not one of ours…”). This book, Les Moissons du Ciel, was recommended recently, and I found it very informative. It’s written by three archaelolgist-pilots who have spent 30 years flying over Brittany searching for sites of interest. There’s a long introduction which I’ve summarised below, then pages of photos with a small caption for each, roughly organised into time periods.

History

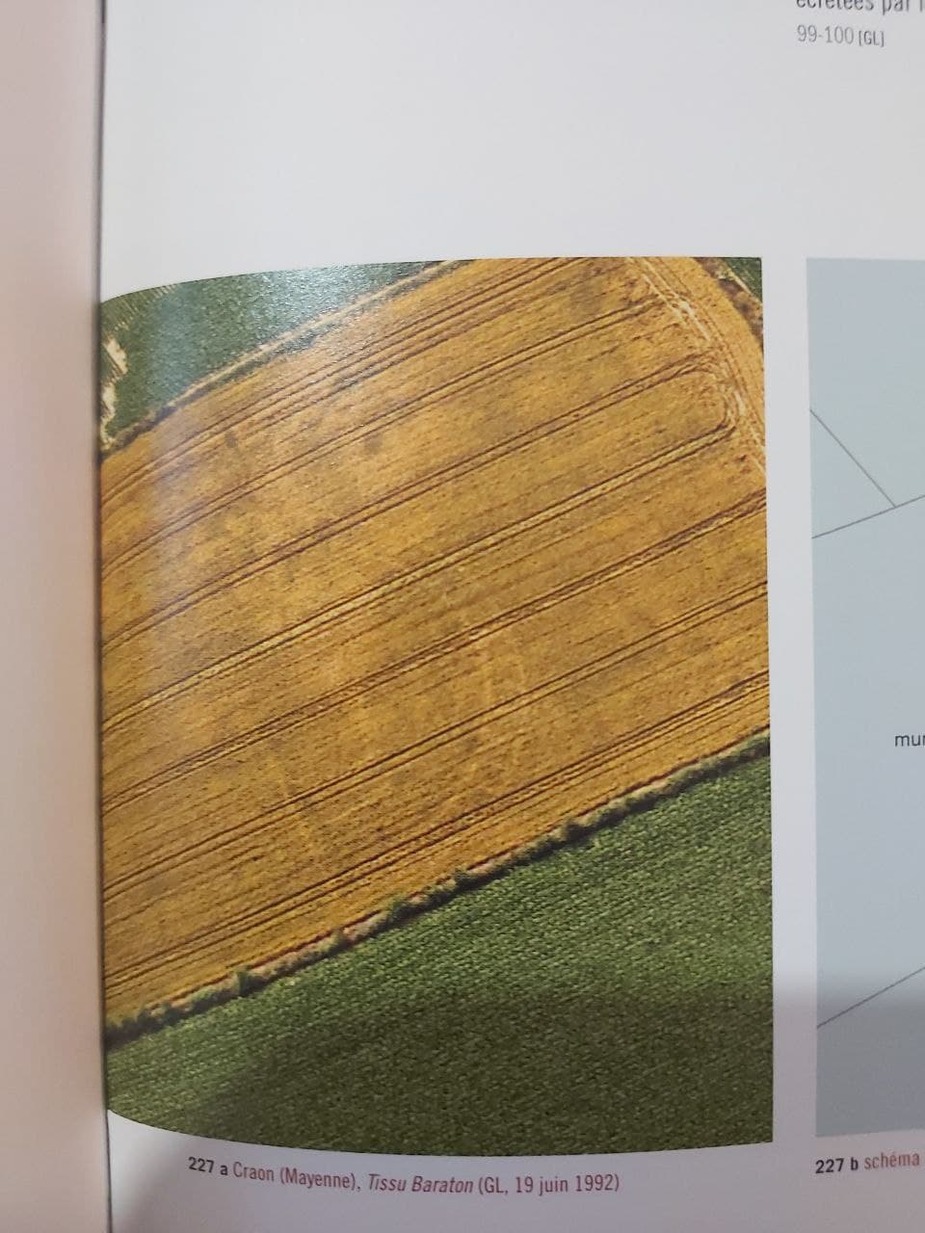

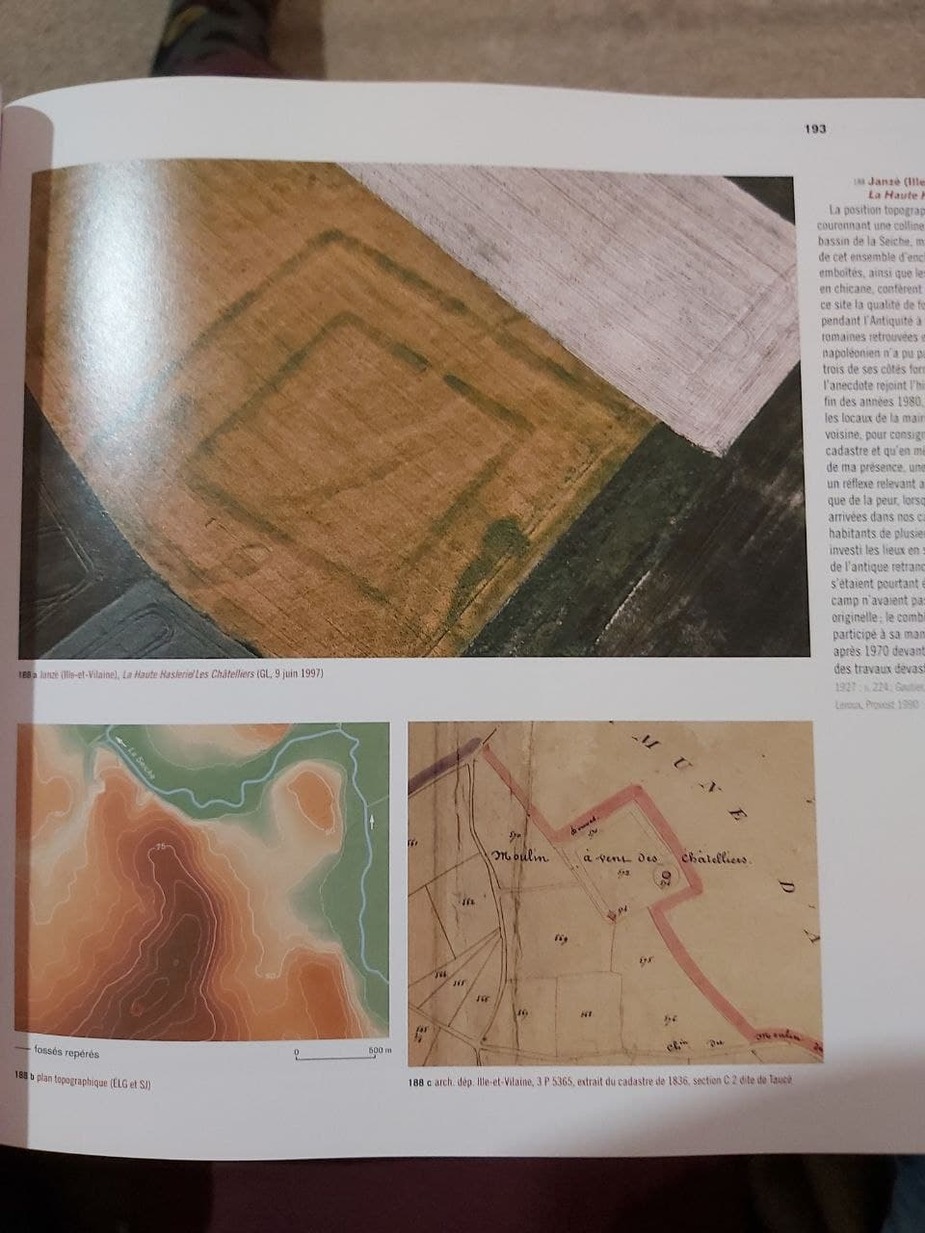

Early pioneers were Poidebard and Crawford, who discovered the limes (the frontier of the Roman Empire) by aeroplane in the deserts of the middle-east. This was thought impossible in Europe after 1,000 years of agriculture, but in actual fact it became apparent that vegetation grows differently over old ditches or buildings, and that these could be identified.

Democratisation

Aerial photography was the domain of the military for a long time due to the cost of aviation and the size of cameras, but democratisation began in the 1960 with Roger Agache (1926-2011) en petit avion d’aéro-club and amateur cameras who freely published his research and findings. In 1973 Archéologia magazine published colour photos of aerial views of ancient monuments, which kept selling out and became the reference work for starting this new discipline. The ‘drought of the century’ in 1976 revealed many previously hidden structures, ditched enclosures, and whole towns and villages which were not to be seen again for 30 years. 1986 saw the start of investment from the départements (local government) for archaeological research and digs. Now, with the internet, preliminary research can be done for free using old maps and plans now available online on IGN with hundreds of layers from the 1700s Cassini map to the current survey and satellite photos.

Recent history

Débocagisation in the area since WWII has removed a large proportion of the ditches and hedges which hid structures, along with drainage operations for land consolidation. Normally both of these are seen as being very negative in all contexts except intensive farming. The term bocage is usually used in English to refer to the unfavourable terrain encountered by the allies in the Cherbourg peninsula after D-day. The urban development of the Rennes basin means it’s now almost completely covered in concrete and many sites have been lost.

Principles of detection

Man-made works, including ditches, post-holes, walls, embankments, worksites, rubble and rubbish leave scars in the soil and sub-soil that can only be seen from the sky. Not all these conditions will be optimal simultaneously, but different years and different seasons will show different things.

Clues:

There are three major factors to finding sites of archaeological interest from the air:

Photos

Taking photos is quite easy with a good pilot and the right plane – high wing with an open window. They use a PA-19, and a C172 with the door removed; in the past they also tried the low-wing Rallye with the canopy open. Cameras with automatic settings and gps massively simplified the photographer’s job. Normal lenses are a 24-75 and 70-200 zoom, both with UV filters.

Weather

Winds of 15-25km/h are ideal to dissipate morning fog or fair-weather haze. Exceptional conditions are just after a cold front has passed, but the cumulus clouds that follow make shadows that interfere with the photos. Early morning dew shows ditches, and late afternoon shadows show crop heights. Overcast skies don’t give enough contrast. Once the structure is found they do a turn or two around it to find the best angle and take photos, and for an overall picture it’s best to create a synthesis from photos taken on different years, seasons, and times of day.

On location

There is 2 metres between tractor wheel tracks, which is a good way to estimate sizes and distances. Comparing to the local plans can help localise the exact location, although sometimes this requires a trip to the local mayor’s office to look at the original plan. Also, a lot of information can be found on the Napoleonic cadastre, if the structure was large enough to be recorded then. Once the sites are located, they are passed to others who sort and organise them to be further investigated by local volunteers by prospecting, metal detectors, Lidar, digging.

Flights

Flights can last 5 hours, but there are many aerodromes around the area to stop at. There is never really a specific plan for the flight: they just go to have a look at what can be seen that day. The pilot and photographer obviously have to get on well, and despite wearing headsets they communicate using hand signals. The manoeuvres can be fast and even brutal, 45-60 degree turns and diving on the target. Passengers normally don’t last more than an hour.

Legal issues

After landing they were once interviewed for two hours by the BGTA (la brigade de gendarmerie des transports aériens) who thought they were doing aerial work without a commercial licence. The investigation was unpleasant for the pilots, photographers and aéroclub, but was closed without further action after 6 months.

False alarms

Modern life can be misinterpreted as ancient structures, e.g. watering circles in fields, cross-country running tracks, and even the foundations of a château built after the Napoleonic survey but demolished before the modern surveys, which is easily mistaken for a roman villa. On one flight they found a massive menhir that unbelievably had never been seen before: they celebrated and registered it as a new historic monument. A month or so later, when archaeologists visited in person, it had completely disappeared. A further flight, then enquiring with local farmers eventually showed that it was a set prop for a tv programme

Discoveries

The authors have discovered 7,600 completely new sites over the last 30 years. These have ranged from a simple listing to hoards of stone axes, gold coins, and pottery production. Generally:

Pre-history (Stone age, Neolithic): megaliths, standing stones, burial mounds e.g. Carnac

Proto-history (Bronze Age): agricultural enclosures

Gauls (Iron Age): buildings, farms, enclosures

Romans: roads, villas, temples

Mediaeval: mottes (raised mounds for building castles)

Something spotted in a field…

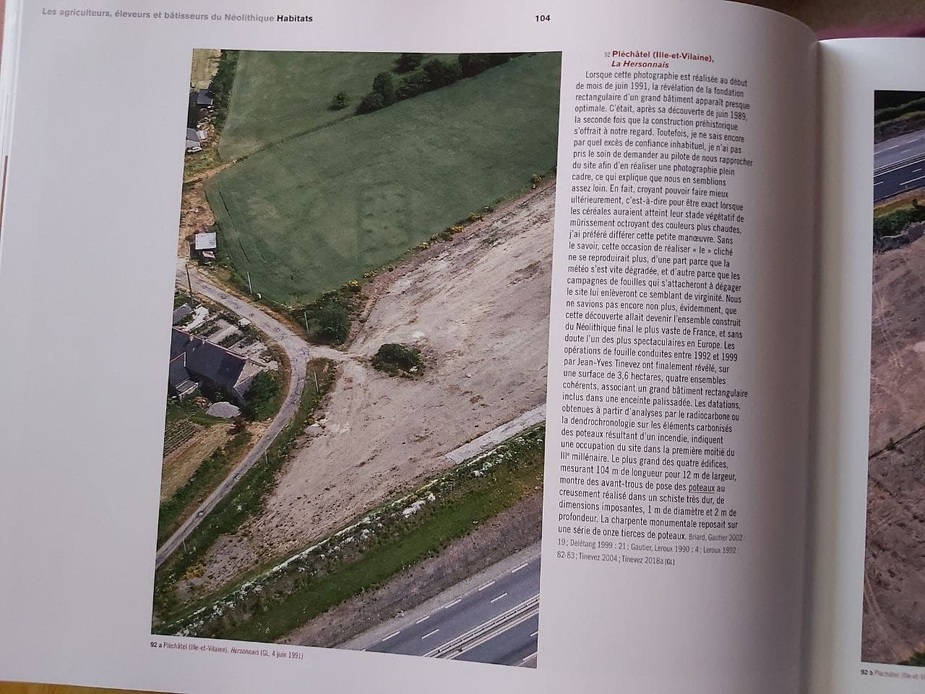

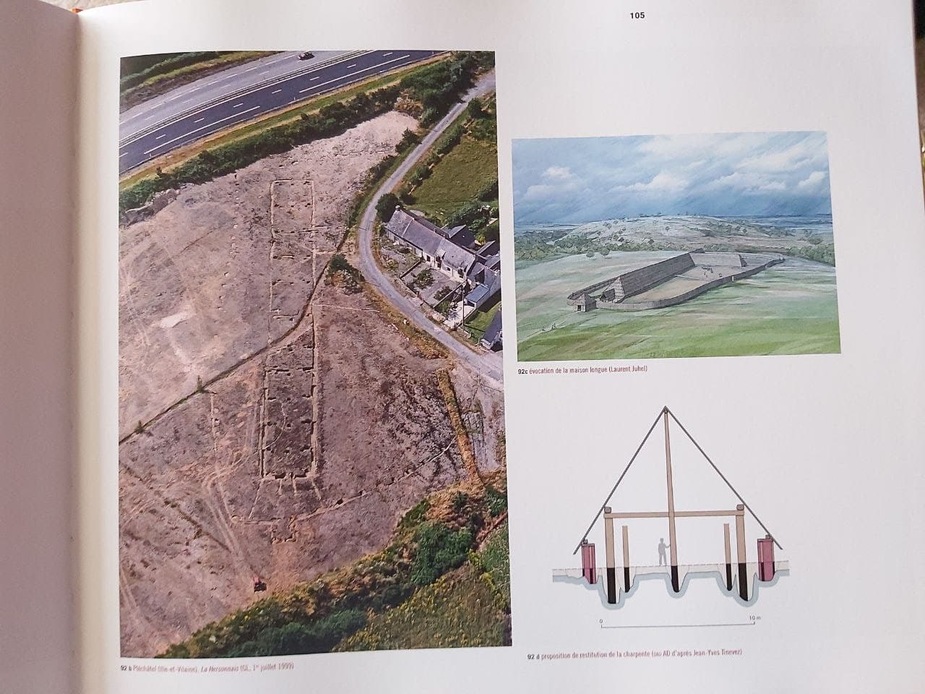

…turned out to be the biggest Neolithic structure in France and probably best in Europe

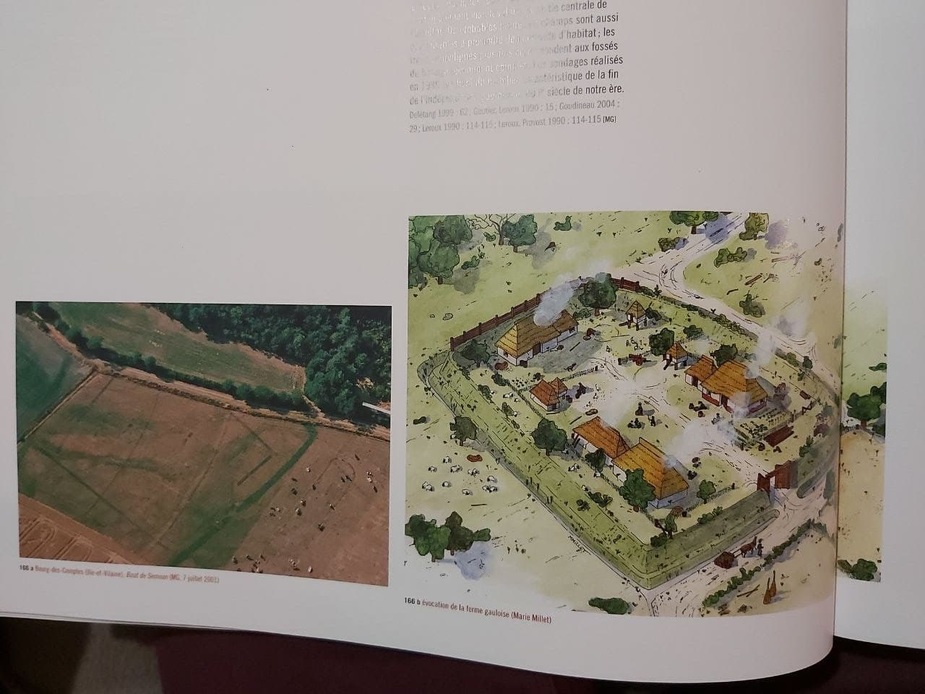

An enclosed farm from (our ancestors) the Gauls

That’s actually a Roman amphitheatre

A discovery on the Napoleonic cadastre

Nice! Many years ago we had a member in my club that did this sort of aerial photography.

Thanks for the inspiration (how to use flying to make the boring archaeology an interesting subject  )

)

Newest “stuff” in aerial archeology is airborne lidar. In south america they found some astonishing buildings and testimonials of ancient civilization. Found this paper about airborne lidar in England where the principals are explained:

This article is about usage of LIDAR in South America:

I regularly see what looks like building outlines in fields, but wouldn’t know what to do of it, if they are already known/researched or not, let alone who to talk to.

Arne wrote:

let alone who to talk to.

Now that would be interesting, if we had anyone to contact. So far I haven’t given it much attention, but if one was to find something new (or old) we should at least have a contact address. Would anybody here know whom to pass such fotos and information?

A closely related discipline is searching for cave entrances in karst regions. In winter, they emit steady streams of warm air, which can be found using airborne thermal imaging. Our airport sits on the edge of Bohemian karst province – if anyone has a thermal camera and wants to try, let me know.

Arne wrote:

I regularly see what looks like building outlines in fields, but wouldn’t know what to do of it, if they are already known/researched or not, let alone who to talk to.

If you see something like that in Sweden you could start by looking at this website: Fornsök

If you zoom in you will find a lot of stuff that has been discovered so far. You will probably also find contact details there if you find something new.

This is a very interesting topic! :)

The first use of the aerial survey was back in 1926 when Squadron Leader G Insall VC discovered the site of Woodhenge on Salisbury plain.

I believe that woodhenge was a sort of prototype for Stonehenge.

This is really interesting.

Around where I live there are many Roman remains which are totally gone unless you know what to look for.

But things can disappear pretty well in 100 years, too. Nearby there are remains of a funicular railway which, while visible from the ground, are probably totally missed by most walkers.

Nowadays I would be extremely careful doing this in the UK, due to the new CAA infringements policy which is absolutely strict; ATC are not allowed any leeway, and on your 3rd occassion you probably get your license suspended. I’ve done various flights in years past, to photograph interesting things, but would not risk it now. With any flight like this I would have a 2nd person watching the GPS 100% of the time, not talking and not looking out of the window.

High-wing is certainly better but if you have clean and undamaged windows in a low-wing, that also works fine. Aerial photography is a whole other topic