Thanks guys! I appreciate the support and I’m here if you have questions.

Does such a thing even exist? A prerequisite is an adequate landing spot,

Yes, of course, you can’t assure a suitable spot.

But I believe it is possible to arrive at the right place, assuming the ground is suitable.

mmgreve wrote:

It has always surprised me that GA teach to trim for best glide…and just let the speed bleed off.

In the airforce we learned to trade speed for altitude. I know there is a little more speed to trade out of an F16, but still.

It was a long time ago and I cannot now recall the detail but I once read an article, in Sport Aviation I think, about trading speed for height in which was given a simple mathematical formula to calculate what you could make. I think it was a function of cruise speed (or the your speed at the point of engine failure) over best glide and for the sort of low end GA machine that I have typically flown the height gain was trivial, maybe 150 feet or so. That might be worthwhile if I was doing a ‘run and break’ over the field but at any height, maybe not so much and I’d have to be right on the ball to exploit it to the fullest.

Fast moving RVs, Lancairs and the like would make more, but again you’d have to be right away into the climb to get the most out of it.

I’m sure Buster1 will be familiar with this.

ChuckGlider wrote:

It was a long time ago and I cannot now recall the detail but I once read an article, in Sport Aviation I think, about trading speed for height in which was given a simple mathematical formula to calculate what you could make

It will always be beneficial to trade speed for alt IMO. The reason is that the overall drag losses will be less, so you will retain the largest amount of energy. And of course, alt is beneficial when looking for a spot to land. For light and draggy aircraft, it hardly makes sense though, as the kinetic energy is eaten up by the drag so fast, no matter what you do. In a draggy microlight you gain 20 feet maybe, while in a Lancair you gain several hundred feet, maybe 1000 or more. Cruising at 2k and gaining 1000 is a huge advantage, gaining 20, not so much.

LeSving wrote:

It will always be beneficial to trade speed for alt IMO.

I object. Usually I would draw this on a white board at our flying school, but here, this mediocre sketch must do.

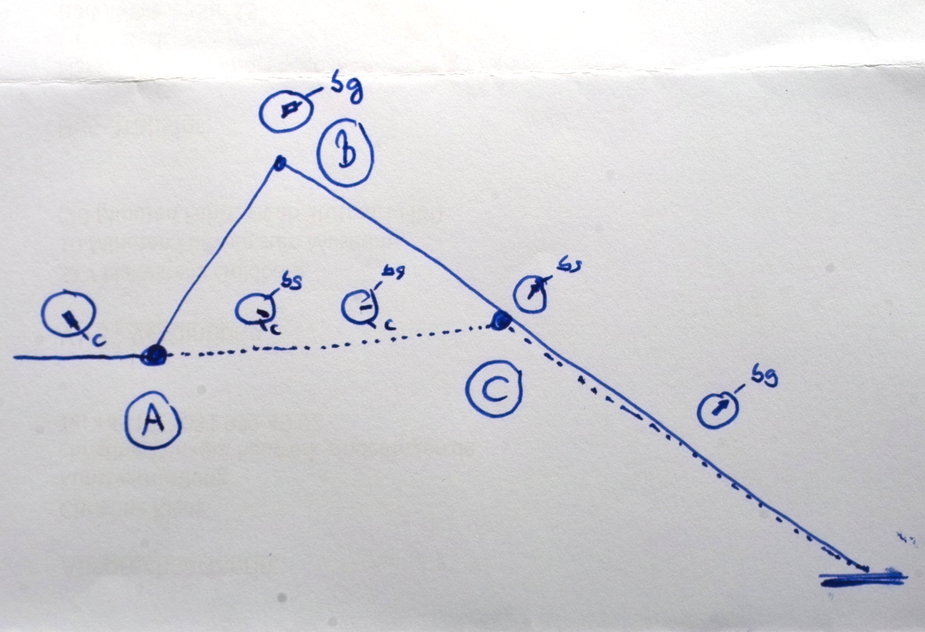

Imagine you are coming from the left at typical cruise speed (the little “c” in the sketchy airspeed indicator) when your engine fails at point “A”.

If you do it military style you will immediately pull up following the solid line until your ASI shows best glide speed (“bg” in the sketch) at point “B” and maintain that until impact.

Doing it the alternative “civilian” way all you (or your autopilot) will do at point A is maintain altitude. Speed will decay until reaching best glide speed at point “C” from which you will glide downwards. The laws of physics (conservation of energy) will see that – provided that all maneuvers are flown smoothly – point “C” will lie on or very close to the “military” flight path.

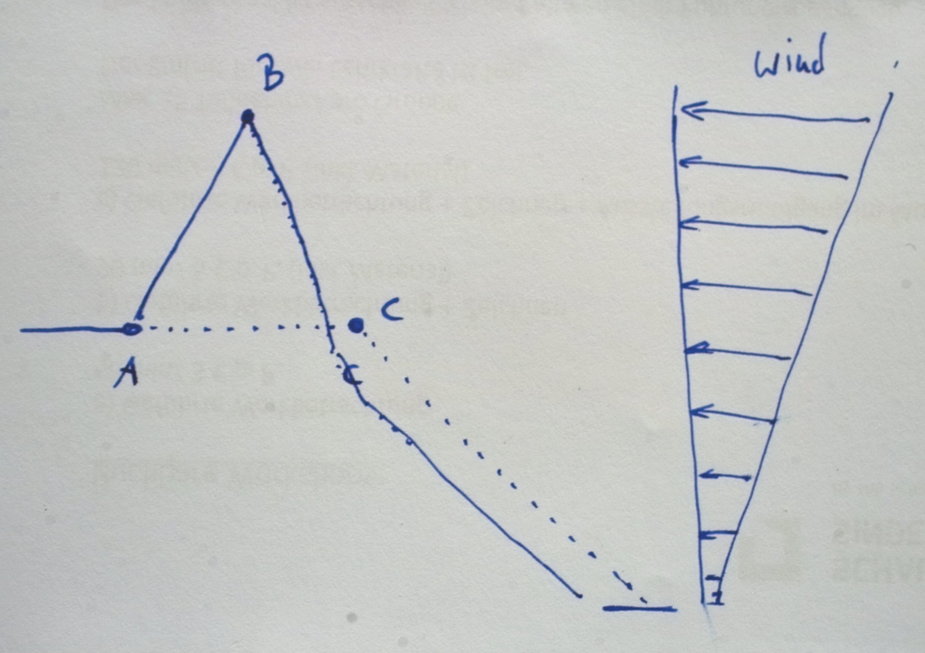

But what will it look like on a typical windy day? With a typical wind gradient at low level, where wind speed at 5000ft will be twice the speed at 2000ft. I have drawn the case where you fly against the wind and it becomes immediately obvious, that our flying soldier will spend a lot of time in a strong headwind, altogether avoided by are peaceful flyer:

Of course with a tailwind the outcome will be in favor of the fighter pilot.

There are a few more reasons why the military profile might not be optimal for an untrained civilian: The maneuver required at point “A” is a sharp(ish) pitch-up. These tend to dissipate quite a lot energy if flown briskly (indeed the militarys use such maneuvers for braking, e.g. in a run-in-and-break procedure). Next, the pitch reversal at point “B” is not likely to be flown perfectly every time: Push over too late and you will come out below best glide speed (which is worse then too fast, gliding distance wise) or even stall if you push very late… Be too fast and you will need to dissipate energy in level flight again – you could just have flown the simpler civilian maneuver in the first place…

Also, the military maneuver requires fast action from the first moment on. Civilians are (purposefully) not trained that way. “Sit on your hands” and look first before acting is what we are taught. In most cases (inflight thrust reverser deployment and “Pull up – Pull up” callouts but the ground proximity warning system are two of the few exceptions) this is the best thing to do. Initially maintaining altitude will give you an extra few seconds to assess the situation and work out your plan B.

My understanding why military flyers do it the way they do is because they often fly at very high speed at very low level. So gaining some altitude before even thinking about gliding to an emergency landing site (of which there are exactly zero suitable ones in my part of the world and I am not aware of a successful military engine out landing with the pilot remaining on board and surviving) is imperative.

What Next,

Excellent discussion and graphics, you are right on the money (as we say).

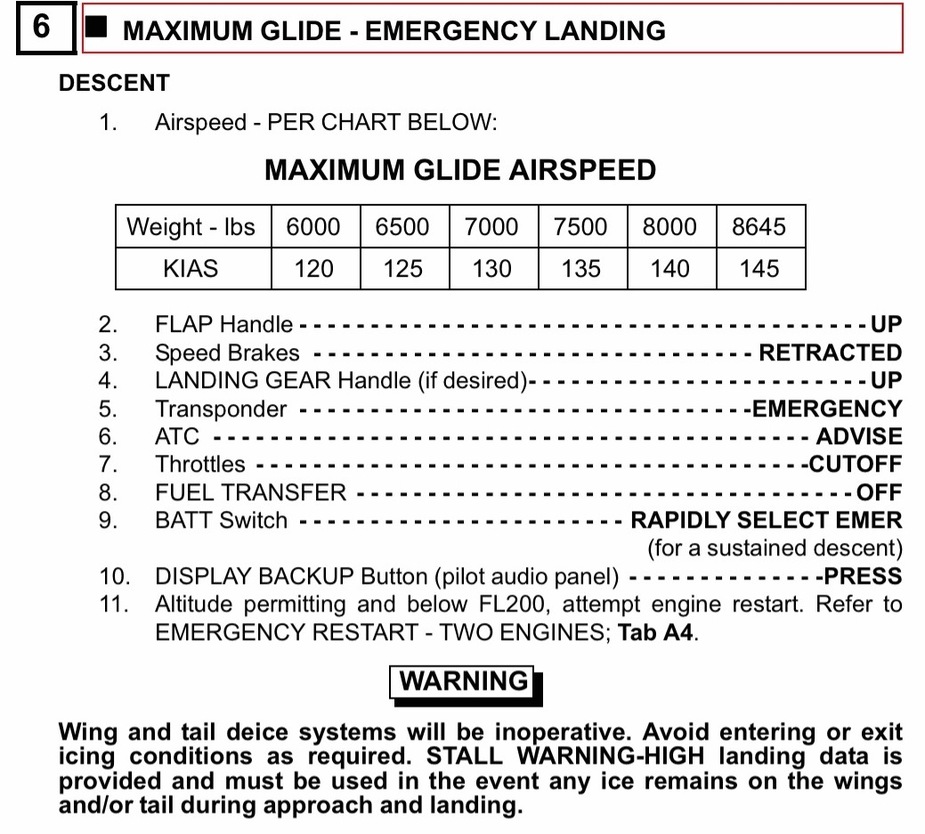

In F-16s we are taught this, and it’s in our manuals as well. If fast, climb to trade airspeed for altitude. 400-500 knots is not uncommon, and our best glide is just over 200 kias, so there is a lot of energy to be had and used by climbing after an engine failure.

In our humble GA singles, not so much. I know I cruise at about 130-140 KIAS in the Bonanza, and my best glide is 90-105 KIAS. So there isn’t much there to gain.

However, if you do lose your engine, and have the SA to climb and trade any excess airspeed for altitude…do it! Good to do! However, typically and without practice or training most of us will overshoot the desired glide speed and get slow. This is common and I see it all the time. This getting slow basically negates any energy gained during the “fly up” maneuver. And that is why it’s often not taught.

But if you can climb and gain airspeed, and get on profile, I recommend it.

Thanks guys! Awesome discussion.

The other reason to trade speed for altitude is when you are not yet sure where you want to try to land, in that case more time aloft without committing to a particular direction could be valuable. At least this thread has made me remind myself of best glide. Not a number you normally focus on in a twin turbine.

By the way, enjoyed the video. Well presented.

I too thought that W-N’s statement

The laws of physics (conservation of energy) will see that – provided that all maneuvers are flown smoothly – point “C” will lie on or very close to the “military” flight path.

might not be quite the whole story.

It is IMHO accurate if the entire maneuver (with, or without the pitch-up) is flown in the same geometric plane. But being simply higher up should increase the range of viable landing sites to one side or the other. It just won’t give you additional landing sites straight ahead (for the aforementioned reason).

The video looks really interesting. I will watch it at home – more data allowance

Peter wrote:

But being simply higher up should increase the range of viable landing sites to one side or the other.

I don’t see the reason for that, honestly. Other than maybe from higher up you have a better overview. Visibility permitting. But as Buster already wrote, the possible altitude gain flying a typical flying club Pa28 or C172 (best glide maybe 75kt, cruise just above 100kt) will be a couple of hundred feet maybe, not something worth considering. Better start aiming at that landing site right away.

IIRC we discussed that “best gliding speed” thing at considerable length already. The odds that you can reach that one any only landing site only by squeezing every last bit of energy out of your aircraft are remote. Most forced landings end with overshoots, not undershoots because the pilot is afraid of dissipating excess engery. It is much more difficult (and almost never trained) to make a good landing at the field which you have just overflown than at one which is exactly at the end of your natural glide path.

At piston GA speeds I agree – but that’s because there is no useful pitch-up benefit.

Also often the engine failure is disguised and not noticed for a while. I have had two occassions and while on one I just happened to be looking at the EDM700 and saw it immediately, on the second one I was doing something else and didn’t notice until the speed bled off a long way. The ALT autopilot mode is to blame  And I suspect this will be true for a lot of fuel or induction air system issues.

And I suspect this will be true for a lot of fuel or induction air system issues.