boscomantico wrote:

Looks like you haven’t dine any real soft field take-offs, then.As Neil said, the numbers in the POHs are useless for the pilot for soft field takeoffs, due to the infinite number of grades of “soft”, which have a huge impact on the take-off run.

The POH numbers for soft field take-offs (usually those for hard runways, plus a fixed markup) are only there for the accident investigator, in order to state, in his report, whether the pilot was at fault or not. Oh, and I guess that insurance experts also use those. But for the pilot, they are useless.

hmm…. the POH at least represents a set of data that can be taken as a margin within to operate. If you don’t have any, then you have to find them out for yourself. I hadn’t realized the Maule didn’t have any figures whatsoever.

I am partly in a similar position. For my plane, upward of a certain serial number, the manufacturer has left any soft / short field takeoff procedure out of the POH. Older models, with similar weights and performances, do have them. So I took these old procedures, tried them out in various kinds of soft fields, and sure enough, they worked just fine. Not flying into or out of soft fields “at all” would be totally and utterly unrealistic.

So, yes, it is my responsibility to make it work, but on the other hand, I do use the values in the POH as a guidelines.

Archie wrote:

On every departure there is a point where the take-off cannot be aborted anymore without injury.

If that would be true, no commercial operation would ever get approved.

Archie wrote:

On every departure there is a point where the take-off cannot be aborted anymore without injury.

Not at all. In most cases with proper runway availability, the take off can be abandoned airborne, and a safe return made. I’ve done it many times (a couple ’cause I had to, and many during testing). It is a certification requirement. However, it does require space.

The requirement that the manufacturer provide takeoff and climb performance data is very much linked to the original certification basis for an aircraft model (as opposed to when that particular aircraft was manufactured). Beyond that, some manufacturers have provided this information optionally. Therefore there can appear to be a disconnect where some models provide the information (typically Cessnas), where others of the same vintage do not – it was not required then. It is required now, and any brand new certified aircraft will state this information in section 5 of the flight manual.

The testing to gather this data is very costly, and post test analysis very involved as well. I did the testing for a modified Caravan, and the data I collected was then analyzed for the required flight manual supplement. The total cost of just this portion of the program exceeded $20,000. Having done a lot of Cessna short field flying, and in particular with STOL modified Cessnas (for which I have never seen revised takeoff data), I hold the opinion that it would be uncommon, and stressful for a pilot to regularly fly an aircraft in and out of runways so short that the short takeoff data was pivotal to a safe operation. I much more believe that Cessna (who have learned to be very liability aware) have provided this data much more so they can point to it after a take off accident and assert that the data was there, and the takeoff could have been safely accomplished within the prevailing conditions. The crash was not the fault of the plane’s design.

The “ground” run portion of the takeoff distance is the easy part. It’s the climb over the obstacle which introduces variability, and the opportunity for error. I opine that many more accidents occur because the obstacle grabs the departing plane out of the sky, than the pilot runs beyond the stated ground run portion of the takeoff distance. But, the “never airborne” accidents do happen, as the recent Caravan into a bridge in China shows. Cessna has also provided water run takeoff distances for some of their floatplane models, though these distances are very much more difficult to measure and apply. Before the advent of Google Earth for measuring your favourite body of water, reference to a very detailed map was needed.

In extreme short takeoff conditions, there are additional tricks to get over the obstacle, which the manufacturer is not going to describe, because they don’t want to be on the hook if a pilot fails while trying. Thus they know that the values which they might present for short takeoff will work, if applied properly.

All that said, be sure that the “document” you are referencing for the performance data is the actual “approved” flight manual or equivalent. I have flown aircraft for which the fancy POH was not the FAA approved flight manual, it was a separate document (both were with the aircraft). the POH contained some extremely optimistic performance figures, which I could not come close to achieving during formal testing. I can only presume that the POH was drafted by an enthusiastic marketing department, ’cause a regular pilot would not likely achieve that performance. On the other hand, I have found Cessna numbers to be very representative of the real world operations.

DavidC (of this parish) posted a nice little video showing a soft field takeoff (second half of the video). With commentary from Jim Thorpe.

Pilot_DAR wrote:

The “ground” run portion of the takeoff distance is the easy part.

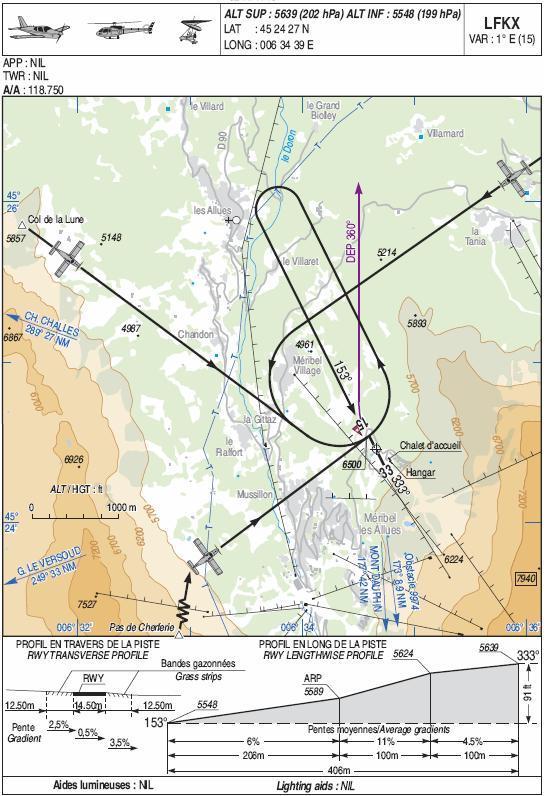

It’s fair to say that none of these is “short” in absolute terms, but I don’t think it is all that easy to use typical POH figures to calculate the ground run at this airport:

or here (270 m @ 10% slope, 5,600 ft AMSL):

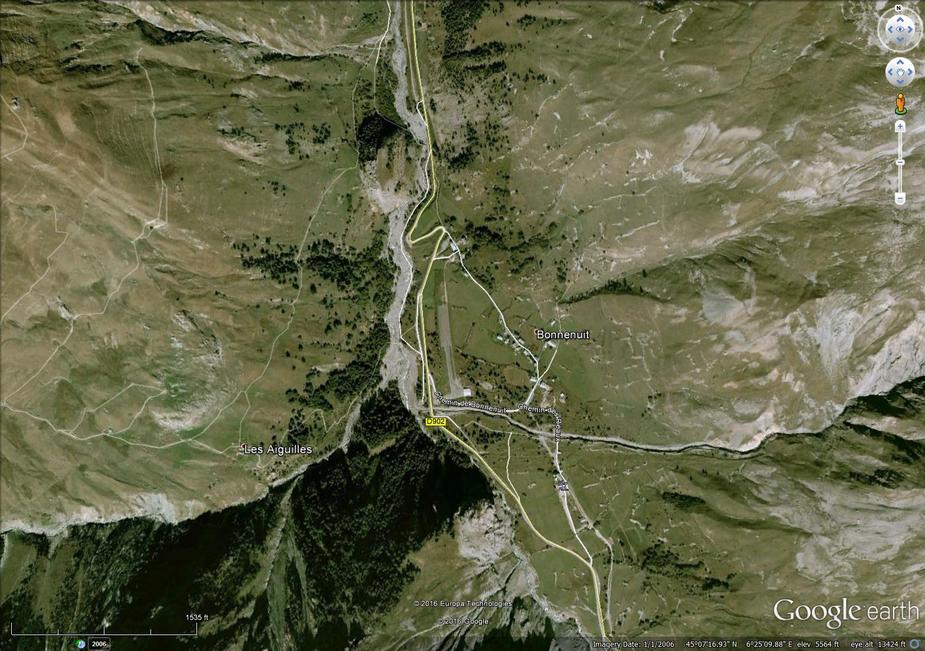

or here (370 m @ 14% slope, 8,000 ft AMSL):

RobertL18C wrote:

Would the rule of thumb that you abort take off if you haven’t reached 75% of your lift off speed at the half way point, work for soft runways?

I think that’s a pretty sound rule of thumb, as long as there is not too much downslope to stop and as long as the runway isn’t particularly soft.

I really don’t trust very soft ground. Even with 31" tyres, once a wheel sinks to the rim, you’re in the civil engineering business. On beaches, intertidal sand can be prone to liquefaction. It’s usually OK as while trundling along in a straight-ish line, but swing the tail around too sharply and the inside wheel suddenly makes its own swamp…

what_next wrote:

If that would be true, no commercial operation would ever get approved.

Obviously it is true. Unless you remain within glide distance of an airfield at all times… (or in a twin). Commercial ops get approved no worries.

Pilot_DAR wrote:

In most cases with proper runway availability, the take off can be abandoned airborne, and a safe return made. I’ve done it many times (a couple ’cause I had to, and many during testing). It is a certification requirement. However, it does require space.

No, same as above. Unless you remain within glide distance of the runway at all times… (I exclude an off-airport landing as it has a high chance of injury). Not sure how certification requirement comes into play?

But perhaps Jacko needs to explain a bit more.

Jacko wrote:

a short field is one where the departure cannot be aborted without injury as soon as the pilot determines that obstacle clearance is not assured

Archie wrote,

I exclude an off-airport landing as it has a high chance of injury

Is this something the Dutch authorities tell GA pilots just to frighten them?

Anyway, from a US or UK perspective, it’s just scaremongering. Searching the NTSB accident database for off-airport GA landings (of which there must be tens of thousands without incident every year) we see very few accidents and even fewer injuries.

I’m happy with my definition of “short” and “soft” fields, especially for places where no other aircraft has ever landed, but does anyone feel inclined to offer a better one for established or partially improved landing strips?

(I exclude an off-airport landing as it has a high chance of injury). ……

- at every take-off there is a point where you cannot abort anymore without injuryQuote

I don’t see the link to injury. It happens on improved runways too. I have thousands of unprepared runway takeoffs, and thousands more off the water, including a few real engine failures, and many simulated ones, and never an injury nor damage. I regularly witness alarming displays of poorly thought out airmanship with pilots feigning “STOL” takeoffs with needless steep climbs after leaving the ground, which are much more likely to result in an injurious crash in the case of an engine failure. This is because pilots are allowing the aircraft to climb away at an airspeed too slow to enter a glide from which a successful flare could be made in time. And all this within the confines of perfectly suitable runways.

It is a certification requirement that an aircraft be able to be safely landed back after a departure engine failure at 50 feet – as long as the pilot achieves the speed needed to accomplish this. Upon reaching, and maintaining that speed, the aircraft can be landed back without damage (surface notwithstanding). Failure to achieve that safe speed is a recipe for a crash if it quits.

When I think back, I would estimate that 999 out of 1000 takeoffs I do would employ a soft field technique, to one employing short field. It is rare that I depart from a runway so short for the aircraft that I worry about having space to clear the obstacle. But, every now and then I’m cautious in this respect. In all other cases, my technique will be soft field, simply to save wear and tear on the landing gear. In a few of those cases, I will use a soft field technique because the runway actually is soft.

I’ve never heard of a requirement to remain within gliding distance of an airfield, but if it’s a rule somewhere, okay – it certainly is not in Canada!

Pilot_DAR wrote:

It is a certification requirement that an aircraft be able to be safely landed back after a departure engine failure at 50 feet – as long as the pilot achieves the speed needed to accomplish this. Upon reaching, and maintaining that speed, the aircraft can be landed back without damage (surface notwithstanding). Failure to achieve that safe speed is a recipe for a crash if it quits.

Hang on, we have a serious misunderstanding here. You simply cannot assume that you can get to 50 ft then abort the take-off and land back without having a serious mishap. TODR is the take-off distance required to a screen height of 50 ft.

What you are talking about is the total sum of distance = TODR + LDR, which is the take-off distance required to 50 ft, followed by a landing again from that 50 ft. And using that as your personal margin. All I can say it that you are applying a margin that is way outside of POH/AFM specifications. Which is not necessarily a bad thing.  However you don’t need to fly like a test pilot to achieve the TODR figures in the POH/AFM. Just being an average pilot will make these work.

However you don’t need to fly like a test pilot to achieve the TODR figures in the POH/AFM. Just being an average pilot will make these work.

Unless you are talking about some unusual certification process that I have never heard of…?

Jacko wrote:

I’m happy with my definition of “short” and “soft” fields, especially for places where no other aircraft has ever landed, but does anyone feel inclined to offer a better one for established or partially improved landing strips?

But let me ask direct questions as that might clarify a few things as I still don’t get your decisionmaking.

When you say: “a short field is one where the departure cannot be aborted without injury as soon as the pilot determines that obstacle clearance is not assured”

- How do you determine that obstacle clearance is assured?

- When do you determine that obstacle clearance is assured?

Archie wrote:

Hang on, we have a serious misunderstanding here. You simply cannot assume that you can get to 50 ft then abort the take-off and land back without having a serious mishap. TODR is the take-off distance required to a screen height of 50 ft.

What you are talking about is the total sum of distance = TODR + LDR, which is the take-off distance required to 50 ft, followed by a landing again from that 50 ft.

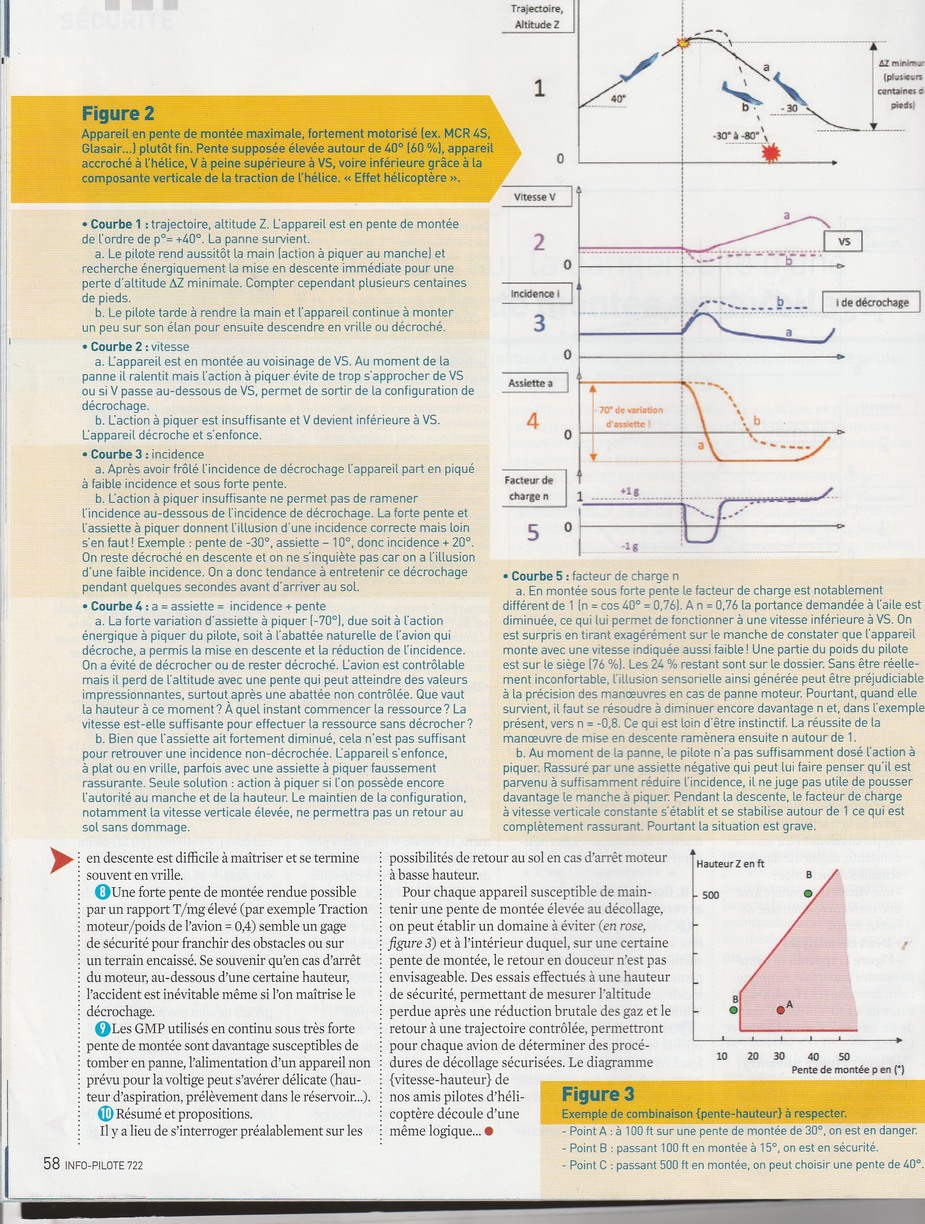

No, he is not. Pilot_DAR talks about a trajectory on takeoff which would allow you to keep flying if the engine stops, as opposed to plummeting to the ground. There was a good article in the May 2016 issue of “Info Pilote” explaining this; unfortunately in French. But if you look at diagrams 2 and 3, you should be able to understand the concept even without reading the text (“facteur de charge” means “load factor”). This is especially pronounced on planes with good motorization and highly charged wings.

In diagram 3 you can see that with more altitude, you can use a steeper climb. But hanging behind the prop (in “helicopter effect”) low to the ground is a recipe for disaster, no matter how much runway you still have in front of you, because you won’t get the nose down before stalling and spinning in.